The surprisingly relevant history of royal summits, in three maps

- In the Middle Ages, international summits between royals could be dangerous, even deadly.

- But in three crucial centuries, things shifted to a friendlier form of personal diplomacy.

- International summits today still reflect the protocol and etiquette established by the end of the 18th century.

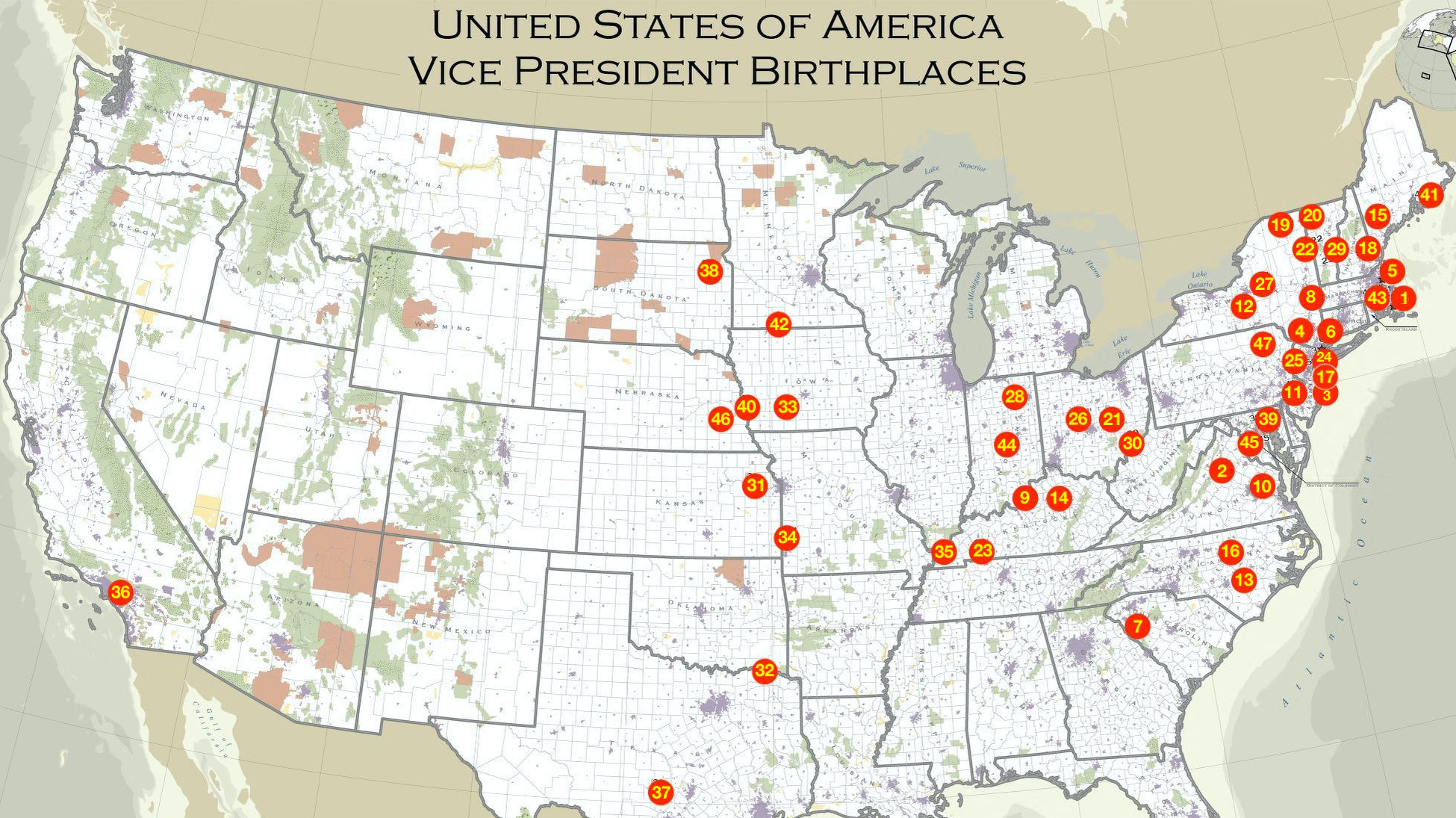

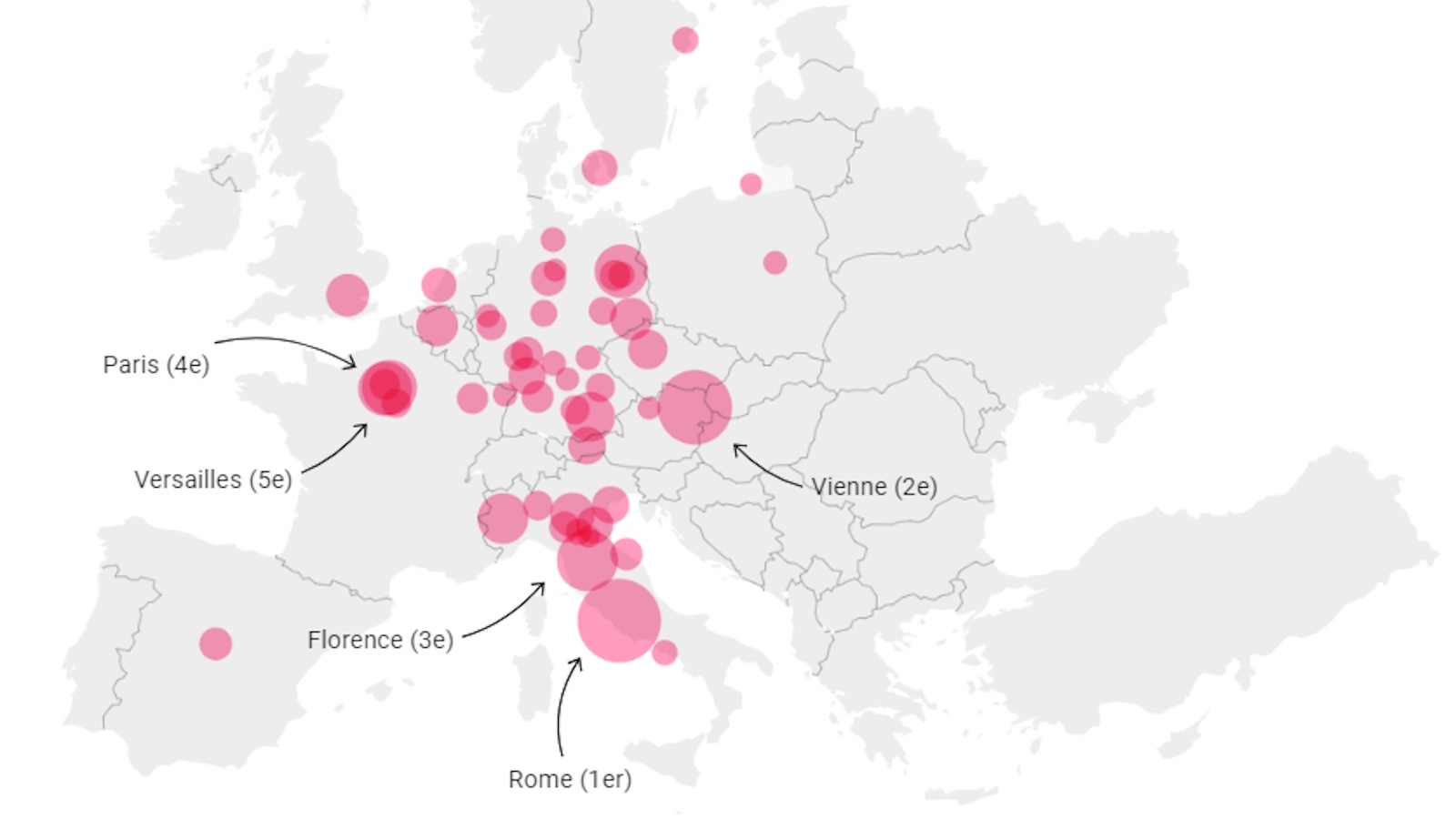

For most of history, international summits were royal affairs. And from the 16th to the 18th centuries, Rome was the favorite meeting place for Europe’s princes, kings, and emperors. As this map shows, the Papal city’s closest rivals were, in descending order: Vienna, Florence, Paris, and Versailles.

From deep mistrust to cordial community

Well down the list are Madrid and London, which is rather surprising, as they were capitals of world empires. In the 16th century, even the modestly sized city of Ferrara in northern Italy hosted more princely meetings than London.

That’s the sort of thing you learn when analyzing 3,344 princely and royal summits in Europe from 1494 to 1789 — which is what French historian Jean-Marie Le Gall did. The big takeaway: Over those three centuries, the atmosphere and style of summitry changed profoundly, from deep mistrust between monarchs to an increasingly cordial community of ruling houses, held together by a universally acknowledged courtly etiquette which Le Gall inventively describes as cosmopolitesse.

For a bit more detail, see this interview with Le Gall in Le Grand Continent, a magazine published by the Groupe d’Études Géopolitiques at the ENS in Paris. For a lot more, read the book he co-wrote with Claude Michaud. For those with less patience, time, or French, see some salient points — and a few maps — below.

Often dangerous, sometimes deadly

Medieval kings met to conduct affairs of state, but did so reluctantly. Royal parleys were often dangerous to travel to, and sometimes deadly to be at. A famous example was the meeting in 1419 between John the Fearless, Duke of Burgundy and Charles, the Dauphin (i.e. heir apparent) of France, on a bridge across the Seine at Montereau. John was killed by the men-at-arms in Charles’s company. In revenge, John’s successor Philip the Good sided with the English against the French in the ongoing Hundred Years’ War.

Short of being killed, monarchs outside their own territory also ran the risk of being taken hostage, held for ransom, or — perhaps most humiliating of all — being outshone by a rival royal and his resplendent retinue. In an atmosphere of general mutual distrust, royal meetings often required a complex system involving preliminary negotiations, hostages, armed escorts, and special passports.

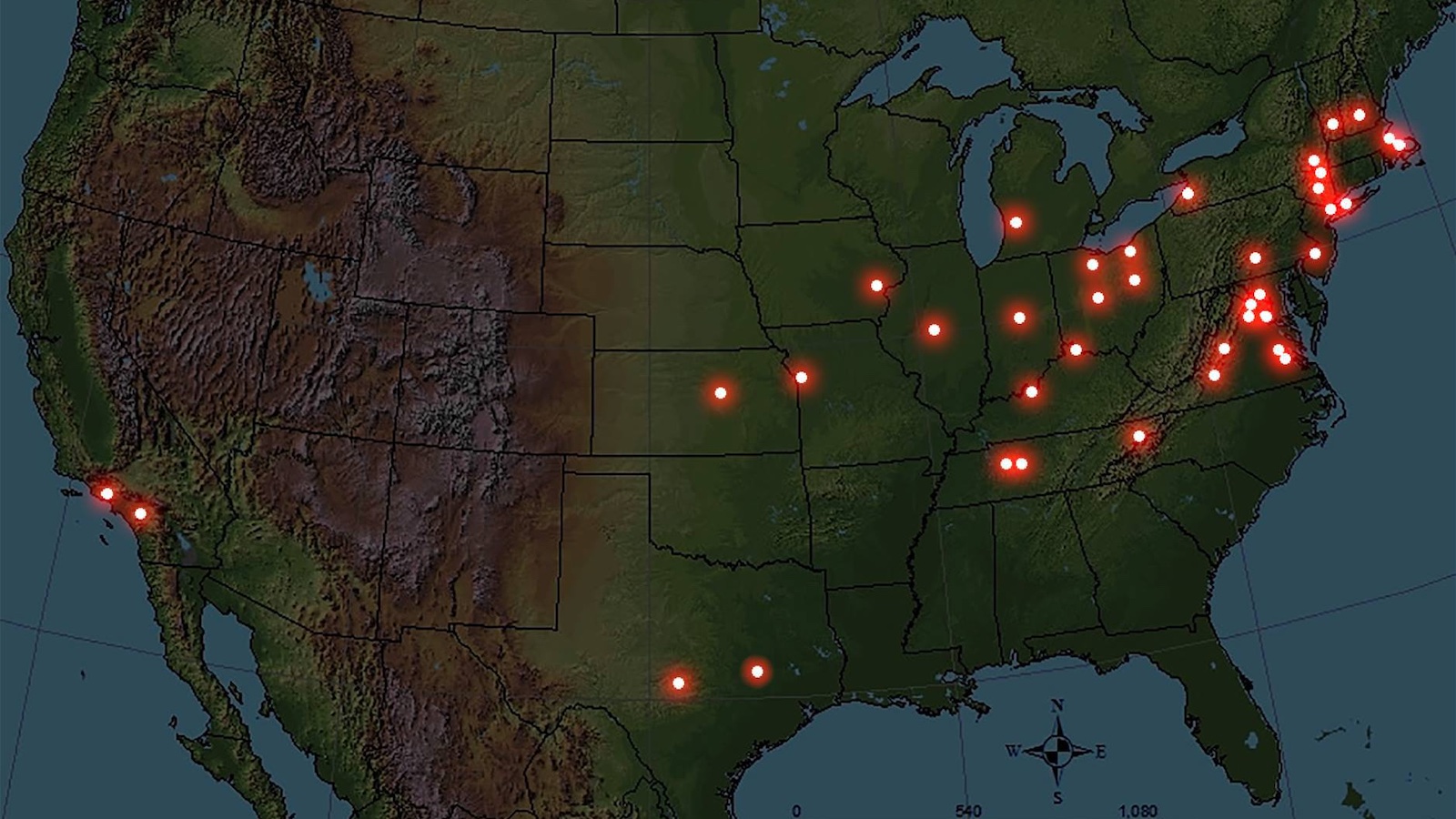

In the Middle Ages, itinerant courts were the norm: Wherever they laid their crown, kings and queens called home. As time went on, monarchs became more sedentary, and the locations of royal summits became more concentrated. These two maps show two extreme examples.

Charles V (1500-1558) was Holy Roman Emperor, and much besides, including but not limited to: King of Spain, Lord of the Netherlands, and Archduke of Austria. The map of his summits reflects the vastness of his estates, as well as the peripatetic nature of his reign. Relatively few of his summits were held in Spain. He spent most of his majestic meetings in the axis between Brussels (his meeting top spot) and Munich, with notable excursions into Italy, while studiously avoiding France, the domain of his monarchical rival.

Louis XIV makes everything about him

What a contrast with the map showing the summits of Louis XIV (1638-1715). He was nicknamed the Sun King because everything revolved around him, and by extension around his court at Versailles, a palace built explicitly (though not exclusively) as a place to attract and dazzle royal and other noble visitors. France is still one of the most centralized states in Europe, a legacy which — despite the passage of centuries and several revolutions — can be traced back to le Roi Soleil.

The Peace of Westphalia (1648) set in motion a sea change in Europe’s geopolitical landscape and in royal summitry. Country-to-country relations were redirected through ambassadors and diplomatic letters. Royal (and princely) meetings became less necessary, but not less frequent. That’s because their nature changed: with state diplomacy now operating in a separate channel, royal summits evolved into an arena for soft power.

Princely meetings benefit both sides of the power differential: Lowly princes received at court get a status bump; courts frequented by many princes rise in status. Each court had its own peculiarities. German princes were less well received at Versailles than Italian dukes, because the French king considered the Germans more beholden to the emperor, his rival.

Europe’s rulers turned the development and maintenance of amicable relations into an art form, thanks to formalized rules of ceremony and hospitality. Rank played an important ceremonial role: Emperors took precedence over kings, kings came before electors, electors outranked grand-dukes, and grand dukes lorded it over dukes.

As the 18th century rolled along, monarchs had become inviolable, and all of Europe was their playground. Le Gall calls that playground “a princely European republic.” And it was an increasingly informal one.

After Westphalia, royal summits turned from matters of war and peace to more domestic topics: marriages and successions. Yes, there were still state banquets and royal processions, but the royals themselves increasingly wanted to break free from the straitjacket of protocol. More and more often, they met outside the circuit of official residences and capitals — in Europe’s spa towns, for example, which included the original one, a town named Spa, now in Belgium.

“Incognito,” but in a different way

A popular pathway to informality was to make an “incognito” visit. That word had a slightly different meaning in this context. It doesn’t mean “undercover.” Going incognito simply allowed royals, while informally still recognized as such, to step outside the strict protocol of hierarchy, which would otherwise prevent them from visiting, say, a literary salon (“ruled” by the lady of the house) or a theater (where the public is “king”).

Incognito visits were often announced in newspapers and drew large audiences, for example when an incognito visiting royal would attend the opera. Such visits were attempts by royals to “court” public opinion, which became an increasingly important method of legitimizing monarchy. (For the few surviving monarchies today, popularity arguably is the sole remaining source of legitimacy.) One of the most famous cases of an “incognito” royal on tour was Russian tsar Peter the Great, who visited Europe variously (but thinly) disguised as a soldier, a sailor, and a carpenter.

From the 17th century onward, a taste for travel as its own goal emerged, and Europe’s princes undertook the Grand Tour, a cultural excursion centered on Italy. Princes would accidentally run into each other on the tour, often with far-reaching consequences. For example, when Maximilian II Emanuel, the Elector of Bavaria, had a chance meeting with the Duke of Savoy in Venice in 1690, he convinced him to join his side in the War of the Grand Alliance against the French.

Despite most heads of state no longer being kings or queens, diplomatic protocol today still follows rules and privileges established in previous centuries. For example, present heads of state on a visit in other countries do not need to present their passport and will not have their baggage searched.

The Queen is dead, long live the Queen

Precedence among heads of state — that is, who gets first place at international events — was a hot potato for centuries. The current system looks at length of tenure. Following the death of Queen Elizabeth II, Denmark’s Queen Margarethe II now is the world’s longest reigning monarch, so she would get the first spot. U.S. president Joe Biden (who assumed office January 20, 2021) is well down the list, behind Moldova’s president Maia Sandu (December 24, 2020), but before Surangei Whipps Jr., the president of Palau (inaugurated one day after Biden).

Codified to universal acceptance, the order of precedence among heads of state is a late example of the shift from mistrust to cosmopolitesse described by Le Gall, thanks to which none of today’s world leaders has to worry about getting their heads bashed in with an axe at a summit, as happened to John the Fearless on that bridge at Montereau.

Strange Maps #1226

Jean-Marie Le Gall & Claude Michaud: Comment la confiance vient aux princes. Les rencontres princières en Europe 1494-1788.

Got a strange map? Let me know at [email protected].