Mapped: The deadly geography of Mount Everest

- Since the early 1920s, more than 330 climbers have died on Mount Everest.

- 200 bodies remain on the mountain, the most famous one being “Green Boots”.

- These maps provide some surprising insights into Everest’s morbid geography.

For almost 20 years, “Green Boots” was a creepy landmark near the summit of Mount Everest. Mountaineers ascending via the north face would invariably pass by this frozen body, huddled into a limestone alcove some 1,150 feet (350 m) below the top. To the live climbers who passed the body, the corpse, still clothed in brightly colored climbing apparel, must have seemed a grim exemplar of the saying that “every corpse on Everest was once a highly motivated individual.”

The blizzard of 1996

Green Boots, arguably the most famous body on Everest, has been identified as Tsewang Paljor, Head Constable of the Indo-Tibetan Border Police (ITBP), though some think it might be his colleague, Lance Naik (i.e. Lance Corporal) Dorje Morup. Both were members of a three-man ITBP climbing party that perished in the infamous blizzard of May 1996, which also took the lives of five other mountaineers.

In 2014, a Chinese expedition moved the body to a more discreet location. Such respect is rare because the harsh conditions on Everest afford so little margin for it. Since 1921, when modern records began, over 330 people are known to have died while attempting to climb Everest. Around 200 are still on the mountain. Recovering their bodies is somewhere between impractical and impossible.

There is something morbidly fascinating about these dead: frozen in time, wedded to the mountain they came here to conquer. The fierce interplay of snow and wind on the slopes of Everest buries these bodies and occasionally exposes them again. Sometimes they tumble down.

The “Sleeping Beauty” of Everest

Some bodies are known landmarks, as Green Boots used to be: “The German” on the second step of the north face route, the “Saluting Man” near the south summit, the “Icefall Body”, in the Khumbu glacier field, and “Sleeping Beauty” on the southeast ridge, until she too was removed from view in 2007.

Zooming out from individual casualties to the overall death toll, the dead of Everest start to form a morbid geography of sorts, which does more than simply horrify. As these maps show, patterns emerge, and lessons can be learned.

The most obvious one is from the sheer number of dead: to be highly motivated is not enough. To climb Everest and make it down alive, you must also come highly trained and prepared, be of sound mind and judgment, and have an appreciable dose of good luck.

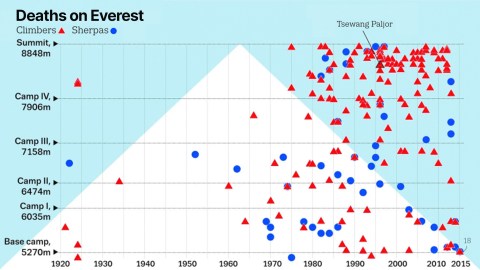

This first map shows the geography of the mountain, with a flag planted for each place where one or more climbers died. This allows us to isolate pockets of danger on the various approaches of the summit:

- The flurry of red flags at the bottom marks the northern end of the Khumbu Icefall, a treacherous, unstable glacier field.

- Further up, amid another bunting of flags, is Lhotse Face, “an extremely dangerous and steep wall of ice.”

- Nearly at the summit is Hillary Step, “a nearly vertical rock face. The last real challenge before reaching the top of the peak.”

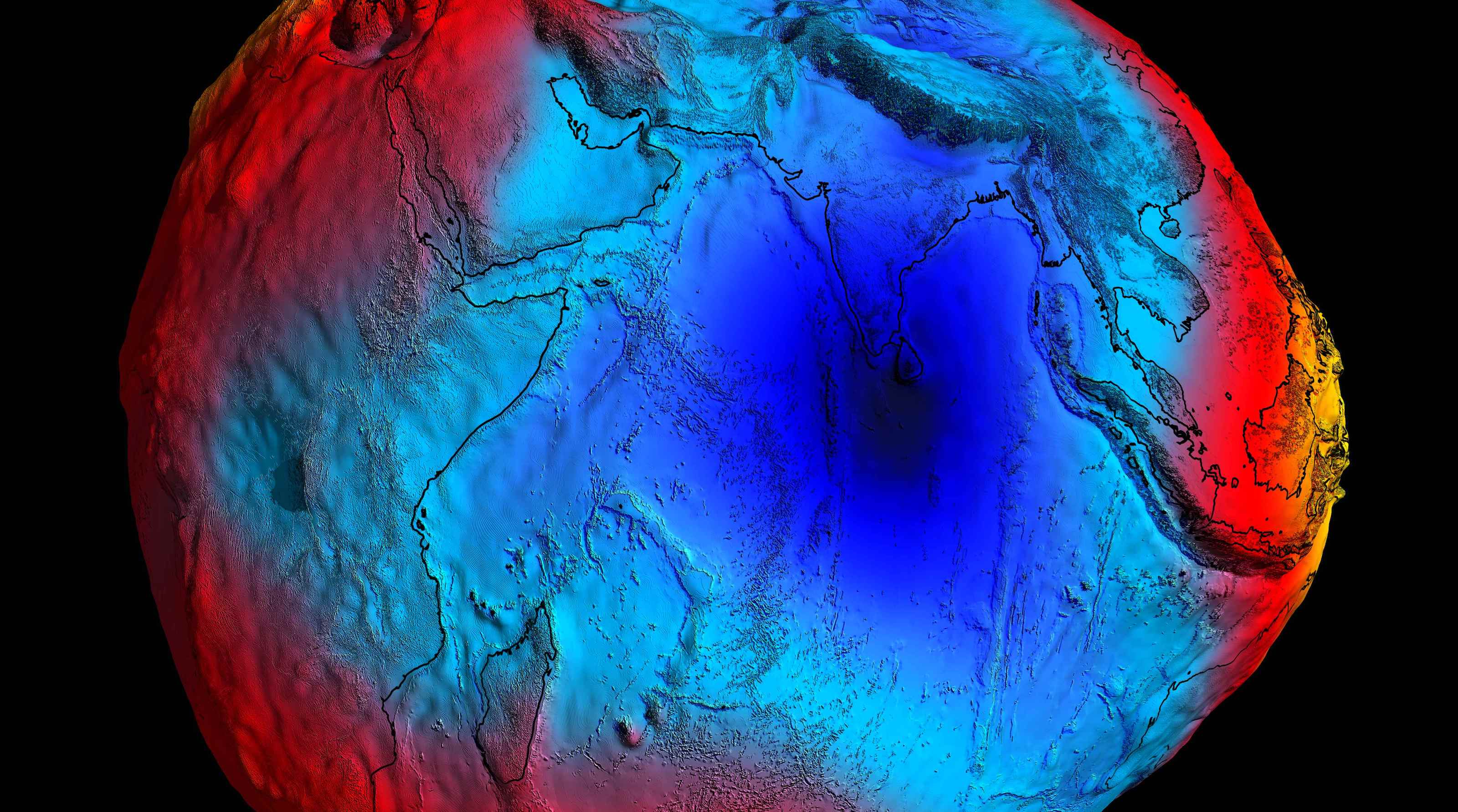

However, as the dotted line suggests, the deadliest factor on Everest is not terrain, but elevation. Everything above 8,000 m (app. 26,250 ft) counts as the “Death Zone,” where the air is too thin to sustain human life for long.

Like being seriously drunk

Climbers who reach this deep-frozen altitude are already exhausted and dehydrated. The lack of oxygen here only adds to their predicament. The effect has been described as “being seriously drunk, but not in a fun way”. Mountaineers not carrying an extra supply of oxygen risk severe impairment of their critical skills due to hypoxia (i.e. oxygen deprivation), leading many to make fatal mistakes. Hence many of those red flags above 8,000 m.

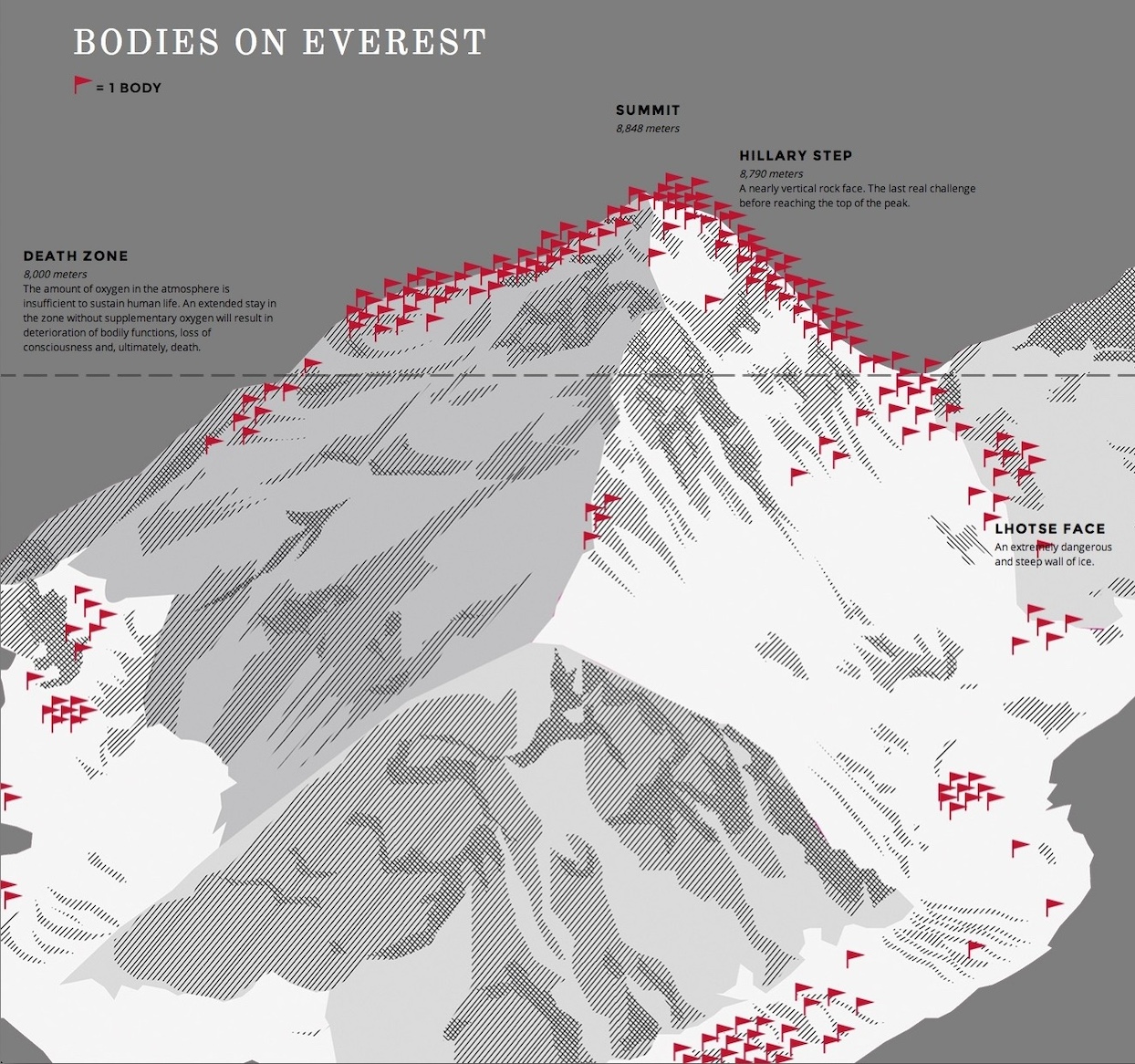

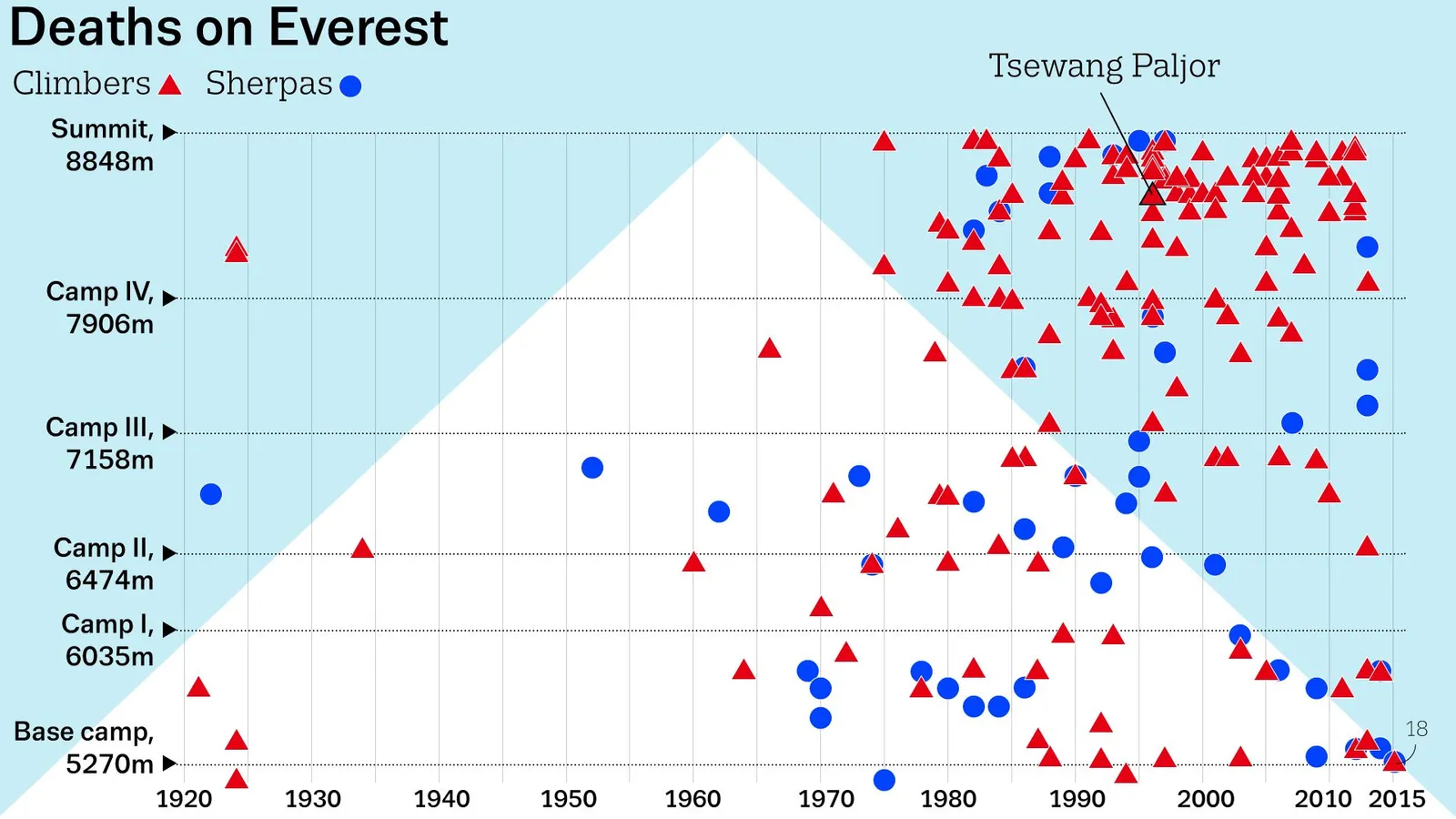

The second map removes the topography of the mountain, but in its abstraction manages to convey multiple layers of information. It shows the year in which mountaineers died on Everest, whether they were visiting climbers or local sherpas, and the elevation at which they died relative to various key reference points on the mountain: Base Camp, Camps I through IV, and the summit. (Note that each dot represents one casualty event, which may have involved more than one death.)

- There are just a handful of casualty events in the first few years after modern records begin. The very first was Alexander Mitchell Kellas (d. 5 June 1921), a noted mountaineer who held the world summit record for 17 years and was one of the first to suggest using oxygen to conquer Everest. He died of a heart attack one day’s hike away from seeing Mount Everest for the first time.

- There were no more than five casualty events between 1925 and 1965, but the tide started turning around 1970, after which the rate of death accelerated.

- Throughout the 1970s, most casualty events still occur below Camp III, but in the 1980s, the emphasis soon shifts upward. By the 1990s, and until 2016 (the end date of this graph), the highest concentration of deadly events is between Camp IV and the summit.

The map shows the elevation and time of death of Green Boots, a.k.a. Tsewang Paljor. It also indicates, in the bottom right, the staggering death toll of an earthquake in 2015, which triggered avalanches that killed 18 climbers (a figure later updated to 22), making it the single deadliest event on Everest so far.

The bigger lessons, however, are twofold. First, there’s an enormous increase in casualties about halfway through the graph, which reflects the rise in absolute numbers in the past half-century of people attempting to climb the mountain, now hundreds every year. The second is the discrepancy between blue dots (the local sherpas) and red triangles (visiting climbers), both in elevation and in numbers. Sherpas tend to die at lower altitudes, while visitors tend to die higher up, and in greater numbers.

Less susceptible to “summit fever”

Why is this? Being local, sherpas are better adapted to life at high altitudes — both physically and in terms of experience — which means they are less susceptible to the problems associated with hypoxia. This includes “summit fever”: the blind urge to continue to the top, even in the face of worsening conditions. A good number of the red triangles near the summit represent non-local climbers who made it all the way up, only to perish on the way down.

Bringing together various types of information on Everest’s victims — time of death, elevation, identity — in abstract form, this map, made for the BBC by Nigel Hawtin, is reminiscent of the Minard map. Often called the greatest infographic ever, it uses half a dozen metrics to provide a damning summary of Napoleon’s disastrous invasion of Russia.

Hawtin’s map dates from 2016, but deaths on Everest have continued every year except 2020, due to pandemic restrictions. It was the first year without casualties since 1977. While most recent years only had single-digit casualty figures, 2023 has proved one of the deadliest years on record, with 17 dead.

In absolute terms, the more than 330 deaths over the past century make Everest the deadliest mountain in the world. In relative terms, however, that title goes to Annapurna in north-central Nepal, the 10th-highest mountain in the world.

Statista calculated that between 1900 and 2022, Annapurna was the target of 244 climbing expeditions, which resulted in 72 deaths. That translates to a deaths-to-expeditions rate of 29.5%. In other words: Three out of every 10 expeditions to Annapurna result in a casualty. That rate is slightly lower for Kangchenjunga (29.1%) and lower still for K2 (22.9%). Everest only comes in at sixth place, with a casualty rate of 14.1%.

Of course, that rate is so much lower because so many more people are tempted to climb Everest. Each one, no doubt, a highly motivated individual.

Strange Maps #1231

Got a strange map? Let me know at [email protected].