The Enlightenment had its own internet: The Republic of Letters

- A virtual, global community? Long before the internet, there was the Republic of Letters.

- The Republic was a network through which many scientists and philosophers communicated in the 17th and 18th centuries.

- Digital analyses of their letters can teach us new things about the Enlightenment — but the method has its own problems.

There was no internet during the Enlightenment, but something surprisingly similar did exist in the 17th and 18th centuries. This was the Republic of Letters: a virtual, global community of scientists and intellectuals who exchanged information using the fastest technology available at the time — the postal service.

15,000 letters

The clue is in the name: letters tied this self-proclaimed, transnational society together. Lots of letters. What this “metaphysical republic” lacked in speed, it made up for in volume. Take Leibniz and Voltaire, for example. In their lifetimes, these great minds wrote close to 15,000 letters each, sending them to hundreds of correspondents across all of Europe.

Ignatius Loyola managed only 9,000 letters, but the founder of the Jesuit order cast his intellectual net much wider. While Leibniz and Voltaire largely limited their correspondence to Europe, Loyola had pen pals from Mexico to Macau, thanks to a global network of Catholic missionaries and other like-minded co-religionists.

This network linking thousands of scientific and philosophical letter writers had a universal protocol: Experiment — not authority — should be the basis for factual knowledge. The network not only spread this ideal but also its fruits: Biological, geological, and astronomical observations from all around the world made their way back to the studies of Europe’s most learned men (and the occasional woman), and eventually into their pamphlets and books.

Of course, all that is now past. Not the experimental method — at least, not yet — but the hand-written letter is as good as dead, killed by almost two centuries of innovations in communication, from social media all the way back to the telegraph.

Sifting through the remains

As one door closes, another opens. Our digital paradigm offers fresh methods of sifting through the remains of the Republic of Letters. With increasing amounts of centuries-old sources digitized, it becomes easier to do quantitative analyses, and to “scrape, mine, curate, analyze, and visualize data.”

That quote is from an article in the AHR Forum about Mapping the Republic of Letters, a collaborative project based at Stanford University that builds case studies based on the metadata of the Republic’s letters. Among the project’s various results are some fascinating maps, some with new insights into the development of the intellectual climate in Enlightenment Europe and beyond.

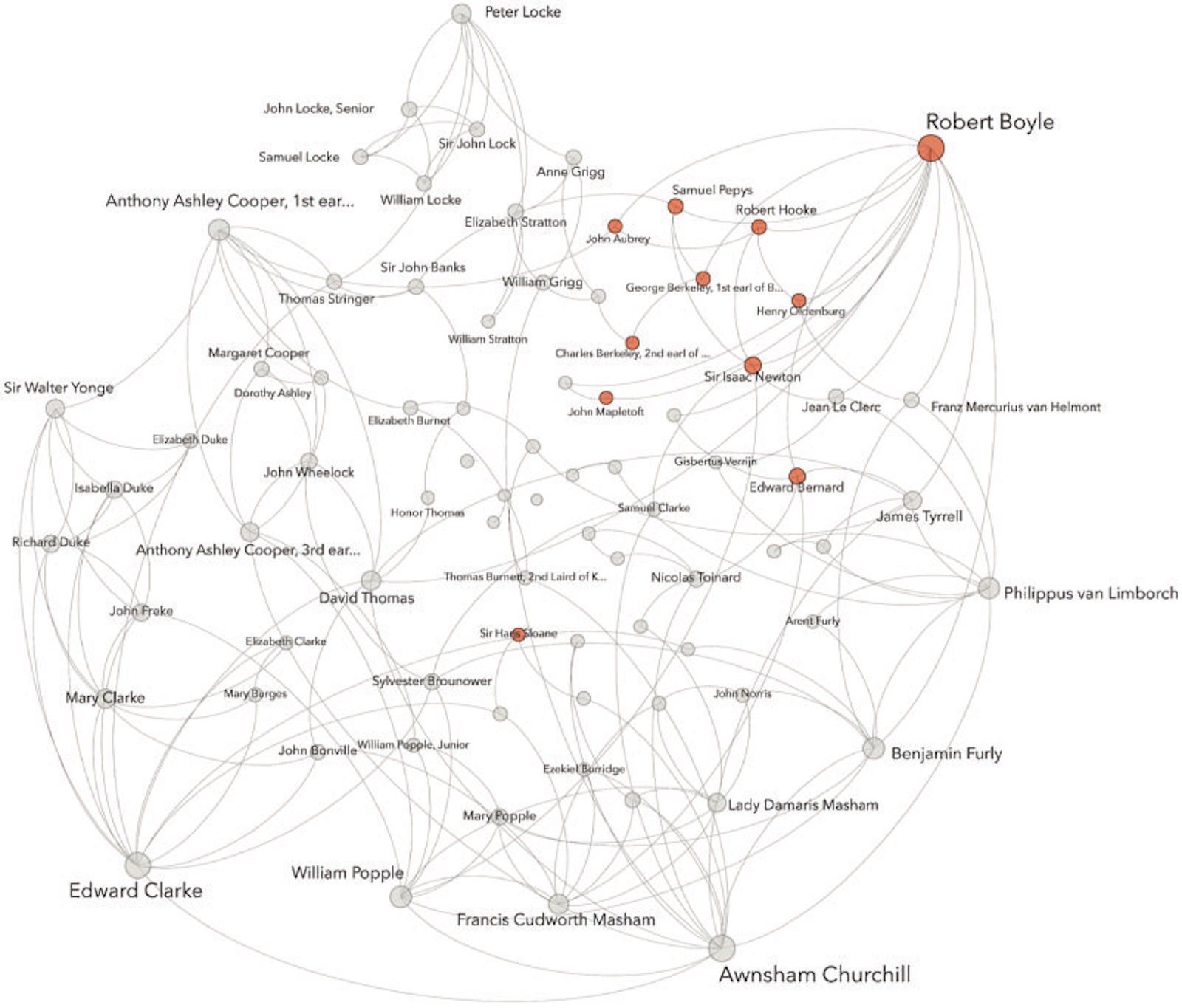

Many of those insights provide a more nuanced picture of the Republic of Letters than we had before. For example, the graph above shows that the Republic of Letters could be better described as a collection of small intellectual fiefdoms rather than as one large whole.

The graph maps the correspondence network of the English philosopher John Locke. It shows just how disconnected the various social and national subgroups in his network were from each other.

A multitude of communities

Rather than everyone writing to everyone, this visual representation clearly shows that several letter writers were the center of their own little epistolary universe, sending and receiving most of their letters to and from a small part of Locke’s total group of correspondents. (Awnsham Churchill, Robert Boyle, Philippus van Limborch — we’re looking at you!)

By demonstrating that there was “a multitude of communities within, or rather underneath, the surface of the Republic of Letters,” this graph offers a valuable corrective to the history of information. Rather than a network, the Republic of Letters was more like a patchwork.

While Enlightenment thinkers liked to style themselves “men of the world,” a meta analysis of their correspondence also calls into question the global nature of the Republic of Letters. Case in point: Benjamin Franklin, arguably the most famous North American of the 18th century, and certainly among the most traveled and best connected.

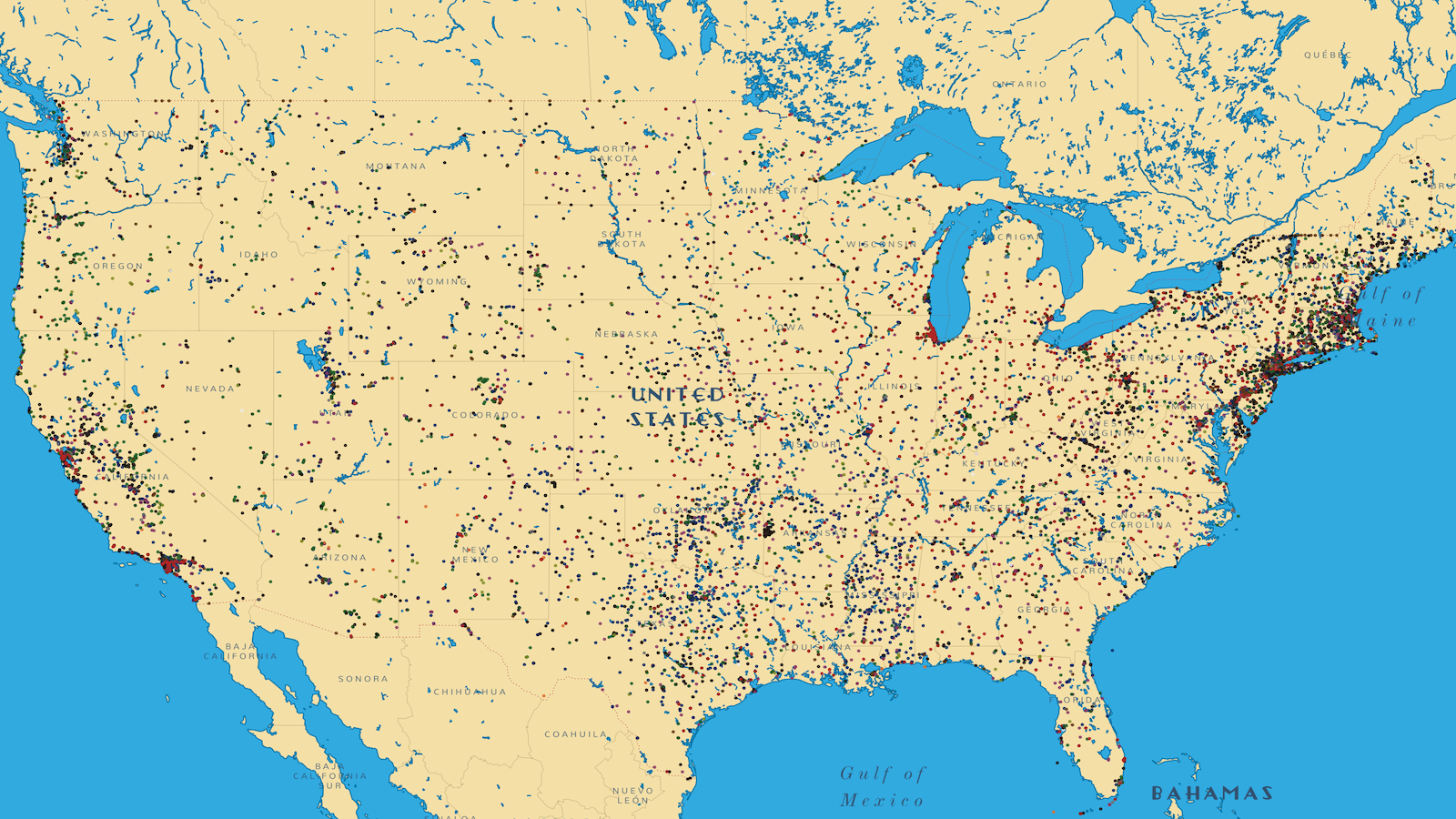

Yet, despite having spent nearly 20 years in London and traveling on the continent, “Franklin’s correspondents were overwhelmingly found at either end of the London-Philadelphia axis,” as this graph demonstrates. Some small forays aside, Franklin’s correspondence doesn’t venture deep into the continent. To be fair, though, the map also clearly shows that Paris was as important a destination for Franklin’s letters as London.

From massive popularity to relative obscurity

It is somewhat ironic that Voltaire, who has been called “the most alive of dead white males,” is remembered these days mainly for a quote misattributed to him. No, he did not say, “I disapprove of what you say, but I will defend to the death your right to say it” (not even in French). The phrase is from a Voltaire biography published in 1906 and was meant to be a summary of his attitude, not a direct quote.

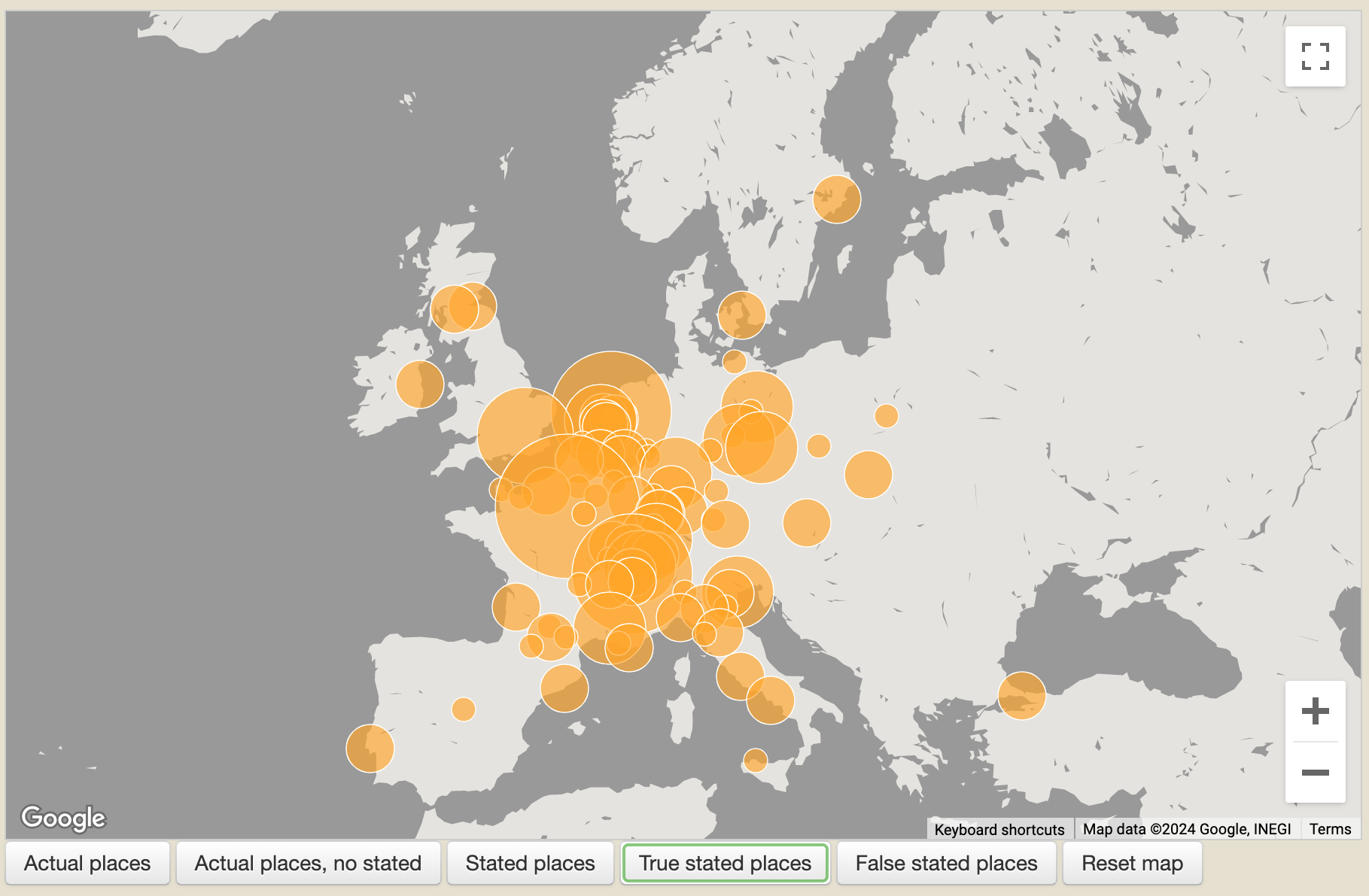

This map highlights the places where Voltaire’s works were published between 1712 and 1800, illustrating his significant popularity during that time, in stark contrast to his relative obscurity today. The total number of publications of Voltaire’s work stands at 1,973, of which 1,370 mention a place of publication. Most of those locations are accurate, but for whatever reason — perhaps to evade censorship — 162 are false…and 10 are made-up “fantasy places.”

Above is another Voltaire-inspired map, this time showing the locations of his correspondents. Paris and Geneva — and to a lesser extent, Berlin, Brussels, and Amsterdam — feature heavily. What’s striking is the near-total absence of addresses in Britain. It’s even more striking when you consider the canonical story of the spread of Enlightenment ideas: from England via Voltaire to the Continent.

Page not found

As this map shows, the absence of correspondence to and from England points to a different story. The mapmakers suggest that Voltaire’s fascination was not with the England of his day but with the reign of Charles II, who had close ties to the court of Louis XIV at Versailles.

Stanford’s project offers tantalizing summaries of other interesting maps and visualizations from the Republic of Letters, but the project’s web page has the distinct look and feel of something that was last updated 10 years ago. Click on something and you’re likely to see “page not found,” or “Adobe Flash player is no longer supported.” Leibniz never had this problem. Perhaps there’s another lesson here for the meta-Enlightenment.

For more on this, check out the full article about Historical Research in a Digital Age: Reflections from the Mapping the Republic of Letters Project, in the American Historical Review.

For the Mapping the Republic of Letters Project itself, what’s left of it, check its page at Stanford University.

Strange Maps #1241

Got a strange map? Let me know at [email protected].