Personalized cancer vaccines are having a moment

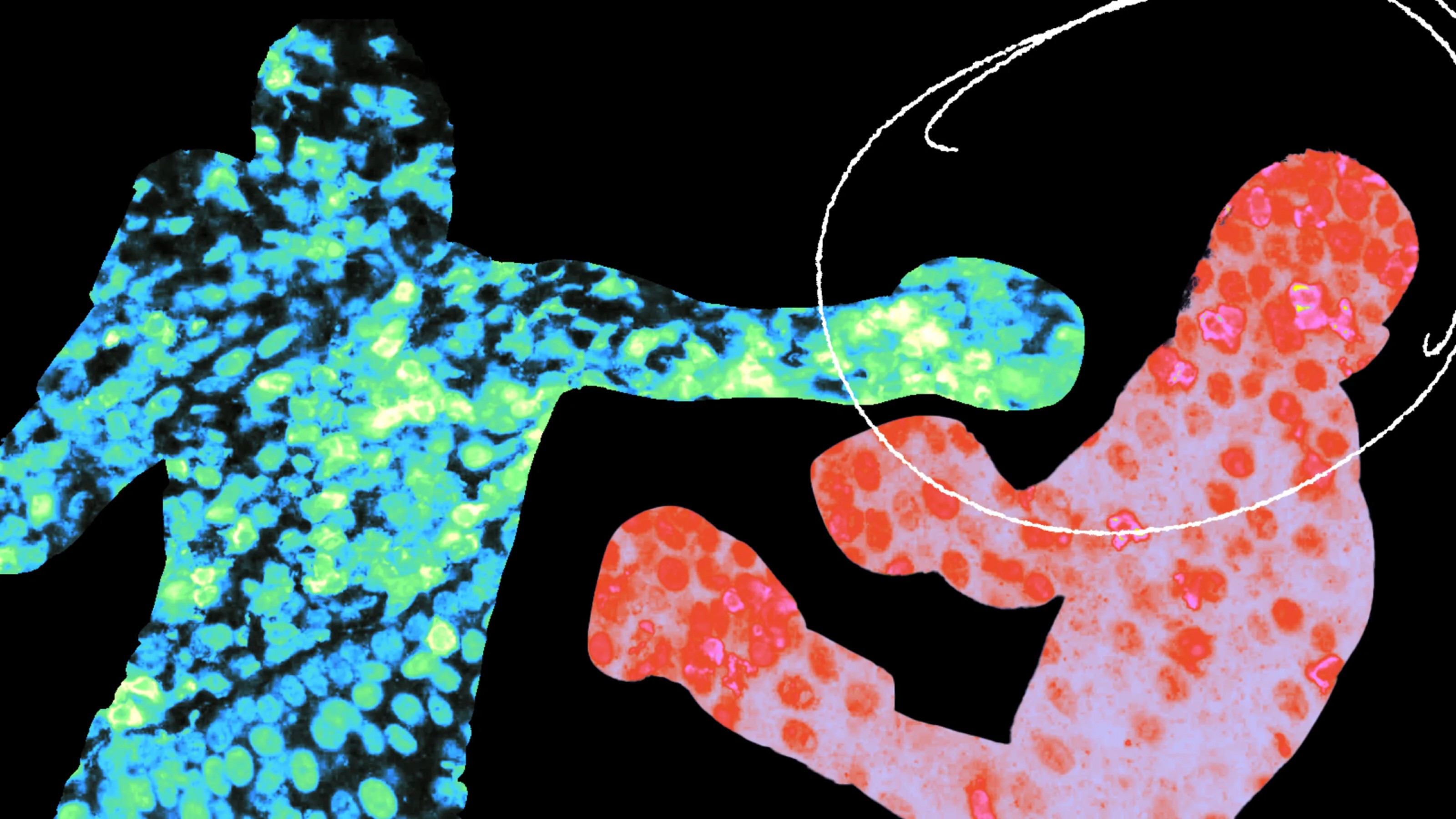

- Personalized cancer vaccines train the immune system to recognize unique proteins on a patient’s cancer cells.

- New personalized vaccines have shown promising results in remission rates for various types of cancers./

- The studies are all early, but if they continue to show promise in larger trials, they may led to a new era in cancer treatment

Promising personalized cancer vaccines were a recurring theme at the American Association for Cancer Research’s (AACR) Annual Meeting in San Diego, earlier this month. A multitude of companies are pushing forward with shots designed to help the immune system fight patients’ specific tumors.

Personalized cancer vaccines: Cancer cells are covered in mutated proteins, called “neoantigens,” that are not found on healthy cells. Personalized cancer vaccines train the immune system to recognize a patient’s unique neoantigens and then find and destroy the cancer cells.

Because researchers need a tumor sample in order to develop one of these cancer vaccines, they can’t be administered to prevent cancer, before a person gets sick. Instead, their purpose is usually to kill cancer cells that might have escaped other treatments, such as surgery or chemo, to lower the risk of recurrence.

The latest: For personalized cancer vaccines to work, they need to target the right neoantigens and trigger a strong immune response, all while being safe and tolerable for patients. After years of mixed results, it seems like the pieces are all starting to come together.

“Because cancers arise from our own cells, it is much harder for the immune system to distinguish proteins in cancer cells as foreign compared with proteins in pathogens like viruses,” said Vinod Balachandran, a pancreatic cancer surgeon-scientist at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center.

“But important advances in cancer biology, the development of novel biotechnologies, and genomic sequencing now make it possible to design vaccines that can tell the difference,” he continued.

Moderna researchers used AACR’s annual meeting to present results from an ongoing trial of an in-development cancer vaccine, called mRNA-4157, which had previously shown promise at preventing recurrence of melanoma.

In the new trial, Moderna is testing the vaccine against a different kind of cancer, called HPV-negative head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HPV- HNSCC). This cancer has a five-year survival rate of less than 50%. In all 22 trial participants, the cancer could not be removed via surgery and was either recurrent or had spread to other parts of their body.

During the trial, patients received infusions of mRNA-4157 combined with pembrolizumab (brand name Keytruda), an FDA-approved cancer immunotherapy. According to Moderna, 14 people experienced some level of disease control, with two going into complete remission.

The median follow-up after treatment was 38.4 weeks, so it’s too soon to gauge the cancer vaccine’s long term impact, but the initial immune response to the combination therapy appears to be better than Ketruda alone in people with HNSCC, suggesting that more research is warranted.

“TG4050 is now starting to show a potential benefit for head and neck cancer patients at high risk of relapse.”

Alessandro Riva

French biotech company Transgene also shared early results from a trial of its personalized cancer vaccine, called TG4050, at the AACR meeting.

This trial tested Transgene’s vaccine in 33 people with HPV- HNSCC that could be removed with surgery. After tumor removal, radiation, and chemotherapy, 17 people were given the vaccine. The rest won’t get it unless their cancer comes back.

After a median follow-up of 18.6 months, none of the people who’d received the vaccine right away had experienced a cancer recurrence, compared to three recurrences in the group that didn’t get it. Adverse events related to the cancer vaccine were mild to moderate.

“TG4050 is now starting to show a potential benefit for head and neck cancer patients at high risk of relapse,” said Alessandro Riva, chairman and CEO of Transgene. “We look forward to starting the Phase II part of the trial in the adjuvant setting for head and neck cancer.”

Biotech companies BioNTech and Genentech also presented promising data on a personalized cancer vaccine, called autogene cevumeran, at AACR’s meeting. It targets pancreatic cancer, which kills 87% of patients within five years of diagnosis.

In their phase 1 trial, 16 patients who’d had pancreatic tumors removed received the vaccine along with chemotherapy and a monoclonal antibody therapy. In 2023, the researchers reported that the vaccine appeared to trigger an immune response in eight of the participants.

It’s now been a median of three years since the vaccine was administered, and of the eight people who appeared to respond to it, only two have had their cancer come back. Of the eight who didn’t respond, seven have experienced a recurrence.

The team has already launched a phase 2 trial that is expected to enroll 260 patients. It will compare the cancer vaccine to a placebo, which will provide a better idea of how well it works.

The big picture: These are all early studies, but if personalized cancer vaccines are able to live up to their promise in larger trials, they could lead to a new era in cancer treatment.

“We are really excited by these preliminary data, as well as by the body of evidence that is being built by the community in favor of neoantigen-based vaccines,” said Transgene researcher Olivier Lantz. “Studies like ours are demonstrating the potential of individualized neoantigen-based therapeutic vaccines to be a part of tomorrow’s standard of care.”

This article was originally published by our sister site, Freethink.