Do wolves harbor the secret to curing dogs’ bowel problems?

- Humans and domesticated dogs have evolved with changing diets, but dogs’ shift to carbohydrate-rich foods has led to gastrointestinal issues due to altered gut microbiomes.

- Unlike their wolf ancestors, modern dogs often suffer from inflammatory bowel conditions, a problem not fully resolved by simply increasing meat intake.

- A new study has identified a Paenibacillus species of bacteria, offering the potential for probiotic treatments to improve dogs’ gut health and reduce veterinary care costs.

One of humans’ key characteristics, and a major reason we’ve been so successful, is that we can adapt to a huge range of environments and lifestyles. For instance, while modern changes in our diet may have caused an increase in certain inflammatory bowel conditions, we can now consume a wide range of calorie-dense, complex foods previously unimaginable to our hunter-gatherer forebears.

Humans have not evolved alone. In our settled agricultural wake, we brought along a whole host of animals. We domesticated the wild. We tamed the beast. One of the first examples of this is the dog. While it might be hard to imagine in some cases, modern dogs do share a common ancestry with the wild gray wolf.

This has been a pretty good deal for the dogs, on the whole, but even pampered dogs are known to suffer from gastrointestinal conditions that their wolf cousins generally do not. One plausible reason is that we give them our processed foods, but they lack an accompanying effective and adaptive gut microbiome to help them deal with them.

Knowing this, a recent study from a team of researchers at Oregon State University-Cascades explored an interesting way to improve dogs’ gut health.

Trouble in the dog bowl

A gray wolf eats predominantly raw meat, hunted or scavenged. So, a wolf’s gut will contain certain microbiota that are specifically designed to aid in digesting carcass meat. The Paenibacillus species of bacteria is the main ally here. This stomach bacteria will produce certain advantageous antimicrobials, antibacterials, and antifungals that improve the overall health of the wolf. For instance, Paenibacillus reduces E. coli in the lower intestine and strengthens the immune system more broadly. In short, Paenibacillus is a good thing for a wolf.

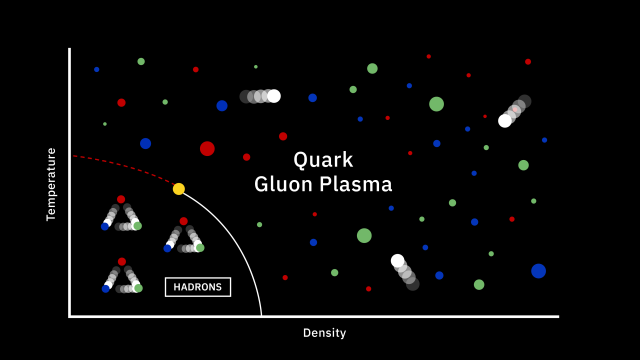

The problem is that when you stop eating only raw meat, your gut biome will adapt. Modern dogs eat a different and more varied diet than gray wolves or their ancestors ever had. Most importantly, domesticated dogs have been eating more food high in carbohydrates made up of cereal grains — in the past, scraps and food waste from humans, and more recently, commercial dog foods.

So, over time, dogs have developed GI tracts suitable for this polysaccharide metabolism. In some ways, our pet companions are better for this diversification of diet because they are exposed to more nutrients, vitamins, and calorific foods. Diets only made up of meat can place strain on the kidneys and cause renal failure.

In one very important way, however, the move from a meat diet to a carbohydrate one exaggerates and multiplies the incidence of inflammatory bowel conditions in modern dogs, by changing their microbiome.

A difficult resolution

If the inflammatory bowel conditions are caused by a deficit in Paenibacillus, and if that in turn caused by eating less meat and more other foods, surely giving your dog more meat would resolve the issue? Sometimes, yes. But as McCabe et al reveal, “even when switched to a raw meat diet, a dog’s fecal microbiota only partially resembles that of a wolf.” You cannot change millennia of canine stomach adaptation with a bit more offal.

You generally cannot currently cure IBCs. Diet changes can and do help, but most cases in dogs are treated with antibiotics or anti-inflammatory medications from the vet. These can be expensive and might have other knock-on effects on a dog’s gut microbiome and general health.

Now, we have a different solution. What the team from Oregan State University-Cascades has discovered is a strain of Paenibacillus that could be turned into an effective prebiotic or probiotic. Up until now, it’s been hard to isolate and locate a suitable microbe to make such a formula, and this novel strain, which the team calls ClWae2A, makes for an optimistic change in fortune. This strain, collected from a freshly killed wolf hit by a car, is able to “encode enzymes that would be of value in digesting carbohydrates and could contribute to energy metabolism for a monogastric animal.”

If you don’t have a dog or you take only passing interest in canine intestinal microbiota, this all might seem a touch irrelevant to you. It’s the parochial esoterica of dog-lovers and biologists. But Americans spend $36 billion on veterinary care, and it can cost around $850 a year to treat IBCs. The pet food industry is estimated to be worth $170 billion by the end of the decade. That’s a lot of money, and it’s just possible that this new discovery, and ones like it, could one day help pet owners treat or prevent this condition. That will make for a lot of happy dogs and happy owners, too.

This article was originally published by our sister site, Freethink.