How Vladimir Putin and Xi Jinping define democracy

- In Putin’s Russia, autocracy is not necessarily seen as incompatible with democracy.

- In Xi’s China, Western democratic values are labeled as bourgeois and an obstacle to the justice of communist rule.

- However, by arguing against human rights “in the Western sense,” these dictators try to hide their indifference of truly universal human rights.

Shortly after Xi Jinping was reelected as China’s head of state in 2022 — by a vote of 2,950 to zero — the Chinese foreign minister Qin Gang criticized U.S. President Joe Biden for contextualizing the event as part of a battle between Western democracies and non-Western autocracies. Gang proclaimed that China, alongside Vladimir Putin’s Russia, was “committed to promoting a multipolar world and greater democracy in international relations.”

Neither politician can be taken at their word, though. Gang’s career is predicated on his loyalty to Xi, for which he was rewarded a promotion to state councilor. Meanwhile, Biden hopes to imbue his reelection campaign against Donald Trump with a sense of existential dread. Motivated by the politics of their respective countries, neither is telling the full story.

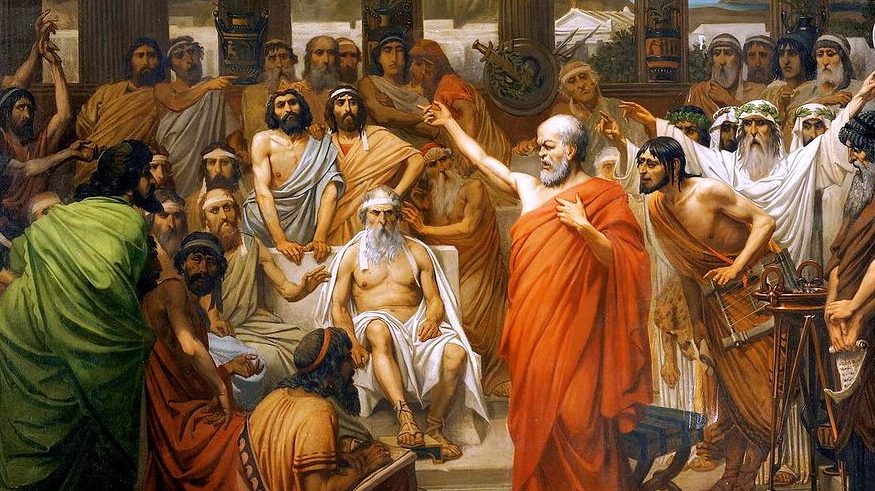

Although modern democratic traditions are closely associated with Europe, originating in ancient Athens and maturing during the Enlightenment, it is wrong to assume that representative government is an inherently Western concept, existentially incompatible with non-Western societies. Such beliefs are readily disproven by the successes of modern-day democracies such as Japan and South Korea — not to mention archeological evidence of democratically structures societies in India, Mexico, and other parts of the world far removed from Grecian shores.

At the same time, it’s worth considering why Xi and Putin, two autocratic leaders who oppress their people to remain in power, jump through such logical and linguistic hoops to present themselves as representative leaders of democratic nations. This seemingly contradictory strategy not only serves to neutralize their internal opposition by giving citizens the illusion of political agency, but also to empower their own positions. Ultimately, Xi and Putin define democracy not as a government elected by the people, but as a government acting on behalf of the people to protect their (supposed) interests.

Democracy in Russia

Putin’s attitudes toward “Western-style” democracy are rooted in Russian history as the country has long identified as distinct from the West. When democratic revolutions toppled Europe’s monarchies, the czars maintained that similar developments could never unfold on Russian soil. Their belief was based partly on self-preservation, but also age-old traditions in Russian philosophy and literature. Russia’s leading thinkers had spent centuries debating whether Russia was European, Asian, or something else entirely. During this age of great uncertainty, the more conservative among them came to see the czar — and, by extension, the absolute power this individual wielded — as the foundation of national identity and representative democracy as its existential enemy.

This way of thinking, repressed under the Soviet Union, has resurfaced with Putin. According to Kathryn Stoner, a senior research fellow at the Freeman Spogli Institute for International Studies and director of the Center on Democracy, Development, and the Rule of Law, it could even explain his political successes. As she states in an article written for the Journal of Democracy:

“Historians tell us that we should not be surprised that Russia has reverted to a repressive autocracy, and that it is not the result of poor governance but the poor soil in which the seeds of democracy had been sown. Given Russia’s inexperience with liberalism, plus its late industrialization and seven decades of communism, we should ask not why its transition toward more liberalized politics failed but why we ever expected it to succeed in the first place. Statistically, […] most autocracies transition to different forms of autocracy rather than to representative, accountable government.”

Putin’s vision for Russia and the Russian state changed as his relationship with the West deteriorated. Inheriting a vulnerable but promising representative government from Boris Yeltsin, Putin spent his first presidential term rebuilding relationships with other countries. It wasn’t until Russia’s economic growth slowed, and his approval ratings plummeted, that these newfound relations deteriorated. Like the endangered czars before him, the former KGB officer designated his democratically elected opponents as enemies, associating the country’s ever-elusive identity with his own person.

From his 2012 reelection onwards, writes Stoner, Putin “presented Russian national identity as distinctively illiberal, socially conservative, and non-‘Anglo Saxon,’ in conscious contrast to the United States and the United Kingdom.” His distrust of Western culture went beyond identity politics: “Liberal ideals and demands for free and fair elections were not indigenous to the Russian nation but rather evil imports from ‘the West.’”

But while Putin might openly define Russia as illiberal, you won’t hear him refer to himself an autocrat. This is because elections — which are still being held despite most countries doubting their integrity — serve as a means of feigning popular support for his rule. Democratically elected or not, Putin claims to act in the interest of the Russian people. Those who disagree, he argues, have been brainwashed by foreign influence.

Democracy in China

In China, attitudes towards the representative governments of the West are interpreted through the lenses of Marxism and Maoism. In a series of articles published in the CCP’s daily newspaper, People’s Daily, succinctly titled “Questions and Answers on the Study of Xi Jinping’s Thoughts on Socialism with Chinese Characteristics in the New Era” and personally approved by Xi, the Chairman articulated these attitudes in perhaps the clearest terms yet.

In one of these articles, Xi explains why China should take a stand against “so-called ‘universal values’ of the West.” As a Marxist, he believes that the history of civilization boils down to a struggle between economic classes, with revolutions changing society from feudalistic to democratic to communistic until all forms of centralized government have been dissolved.

“While the stage of ‘feudal autocracy’ was defeated by the more progressive stage of bourgeois revolutions, the stage of bourgeois liberalism was, or should be, in turn defeated by Marxist socialism,” the sociologist Massimo Introvigne tells Big Think.

He adds that during the bourgeois revolutions, values such as freedom, democracy, and human rights were progressive. “However, within the framework of the Marxist dialectical theory of history, the same values, which were once progressive, became reactionary in the next historical stage.”

Accusing the U.S. and other Western countries of promoting values specific to their cultures as universal, Xi sees China as being under attack by imperialist forces. Chinese officials have repeatedly asserted that the West does not believe in its own rhetoric, pointing to the latter’s history of systemic racism and catastrophic military operations. Instead of freedom, democracy, and human rights, Xi prefers to speak of universal values like peace, development, and justice.

Unsurprisingly, non-communists do not find Xi’s argument convincing. “This is the excuse of all totalitarian regimes that refuse to grant to their victims human rights, freedom, and democracy,” Introvigne comments. “They claim that these are ‘Western’ values and cannot be applied universally. Xi Jinping’s words are music to the ears of all dictators in the world, and this is why they support China at the United Nations when its abysmally low human rights record is denounced.”

Spirit of the laws

Even before Mao Zedong established the People’s Republic of China, Chinese thinkers saw their society and its political needs as different from the West. The late 19th-century translator and writer Yan Fu, known for his translations of texts such as John Stuart Mill’s On Liberty and Baron de Montesquieu’s Spirit of the Laws, wrote that although democracy was crucial to China’s security, the kind of system used in Europe and the U.S. could not simply be transported to the Far East. Adjustments had to be made for the region’s varied history, culture, and spiritual sensibility.

There is some truth to this. No one model of democracy can be transported effortlessly between countries. Even among Western societies, democracies developed differently based on a country’s respective history and culture, such as in the U.S. and the United Kingdom. The same is true for Asian democracies such as Japan and Taiwan.

It is also important to recognize that Western culture does not have a monopoly on democratic thought. Studies in comparative government, especially the governments of the developing world, can help rectify this misgiving.

However, recognition of these truths should not be an excuse for the human rights abuses committed by Russia and China today.

In an age where Western societies seek to alternately forget, amend, and apologize for its imperialist past, it’s tempting to give into the seemingly politically correct notion that different cultures can define democracy how they choose. In truth, democracy requires power to be vested in the people and exercised through free and fair elections. Without meeting that basic requirement, any other definition — including that of governments acting on behalf of its citizens — can be spun to justify human rights abuses.

As Introvigne concludes:

“The CCP may insist there are no freedom, democracy, and human rights ‘in the Western sense’ in China, and that these words have a different meaning in the Chinese (or Russian, or Arab) tradition and political system. This, however, is precisely what the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and the modern theory of human rights denied, after the Nazis similarly claimed that human rights were not universal and that Germany had its own different tradition.

“There are no ‘Western’ or ‘Eastern’ human rights. There are only the rights humans should enjoy as humans, rooted in the common human nature rather than in an historical tradition or political system. Either they are respected or they are not respected. Xi Jinping is telling the world China does not and will not respect them – if only the world would listen.”