Should we cancel political parties?

In 1796, President George Washington lambasted political parties for allowing “cunning, ambitious, and unprincipled men” to “subvert the power of the people.”

His indictment seems brutally timely today, just a few months after 147 Republican US congress members publicly challenged the results of a free and fair general election. But even long before then, many Americans shared Washington’s concern. The popularity of parties is at a nadir, with both the Democratic and Republican parties widely condemned as not only unrepresentative but also hopelessly corrupt and hijacked by elites. Indeed, a steadily increasing share of American voters — 38 percent in 2018 — are identifying as unaffiliated with either party. That proportion is now larger than the share of voters identifying with either Republicans or Democrats. Asked why he thought Donald Trump was “charismatic,” TV talk show host Bill Maher said: “I think it’s because he hates both parties.”

It seems to be an international phenomenon. In Europe, for example, traditionally powerful center-left parties are being accused of ignoring their voters, potentially contributing to a backlash that helped push the United Kingdom into Brexit.

“People in politics often try to go around parties, to go directly to the people, but without the parties, we’d have chaos.”

Nancy Rosenblum

The mounting animosity toward the parties has inspired debate among political scientists. Defenders of the traditional party system contend that democracy depends on strong, organized and trustworthy political factions. “People in politics often try to go around parties, to go directly to the people. But without the parties, we’d have chaos,” says Harvard University political scientist Nancy Rosenblum, who explored the challenges facing political parties today in the 2020 Annual Review of Political Science.

Yet a small group of scholars, many of them young, say it’s time to start visualizing a more open and direct democracy, with less mediation by parties and professional politicians. Such proposals were seen as “completely fringe” until a decade ago, says Hélène Landemore, a political scientist at Yale University. But events including the 2008 economic crisis and Trump’s 2016 election as president, she says, have enlarged the scope of debate.

Several trends have sped the declining popularity and power of the parties in the United States. Party-run patronage schemes that rewarded supporters with government jobs have long given way to more meritocratic systems. The rise of independent political action committees has given candidates a source of campaign funding — around $4.5 billion in the last decade — outside the party channels that once dominated access to campaign money. This has made many candidates more entrepreneurial and less beholden to the party bureaucracy.

Thirdly, parties now determine their candidates through primary elections instead of with meetings of party insiders. Just 17 primaries were held in 1968; today every state has a primary or caucus. This switch to universal primaries has shifted influence from party veterans to more extremist activists, who are more likely than average voters to vote in primaries, says Ian Shapiro, a political scientist at Yale. In 2018, the Democratic National Committee even cut back on the influence of superdelegates, the hundreds of party VIPs who also had votes in selecting candidates. This was to reassure voters that party officials were listening to them, party vice-chair Michael Blake said at the time.

In many parts of the United States, partisan gerrymandering has contributed to making candidates less representative of their constituents by creating “safe seats” for both parties. That means that the winners are, in effect, decided in the primaries that pit Democrats against Democrats and Republicans against Republicans. This phenomenon helps explain the 2018 election of Alexandra Ocasio-Cortez, then a 28-year-old democratic socialist who had never before held elected office, says Shapiro. Ocasio-Cortez beat an establishment Democrat in a primary in which less than 12 percent of voters turned out.

Not everyone agrees that political parties are weaker today than they once were. Today’s extreme polarization means that much of the public is more strongly attached to their own party, says Rosenblum, and party-led voter suppression or voter mobilization efforts in fact make party leaders more powerful than ever.

Still, Shapiro and many other experts believe political parties have suffered a major loss in clout, which in turn has been a loss for democracy in general.

“Political parties are the core institution of democratic accountability because parties, not the individuals who support or comprise them, can offer competing visions of the public good,” write Shapiro and his Yale colleague, Frances Rosenbluth, in a 2018 opinion piece for The American Interest. Voters, they argue, have neither the time nor the background to research costs and benefits of policies and weigh their personal interests against what’s best for the majority in the long run.

To show what can go wrong with single-issue voting that lacks party guidance, Shapiro and Rosenbluth point to California’s notorious Proposition 13, a 1978 ballot initiative that sharply restricted increases in property taxes. At first, the measure seemed like a win to many voters. Yet over the years, the new rule also decimated local budgets to the point where California’s per-pupil school spending now ranks near the bottom of a list of the 50 states.

Parties serve many other important roles, including facilitating compromise, says Russell Muirhead, a political scientist at Dartmouth University and Rosenblum’s coauthor. As an example, Muirhead points to the US Farm Bill, which the two parties renegotiate roughly every five years. Each time they sit down, “the Democrats want food support for urban people and Republicans want support for farmers, and somehow they always come to an agreement,” Muirhead says. “The alternative is favoring one side or simply passing nothing at all.”

Perhaps most important, America’s two main parties have traditionally cooperated in acknowledging their opponents’ legitimacy, as Rosenblum and Muirhead write. Other nations, such as Thailand, Turkey and Germany, have banned political parties that their governments have seen as too destabilizing to democracy. American parties’ cooperation has helped keep the peace by reassuring US voters that even if they lose today, they may well win tomorrow. Now, however, this fundamental rule is being broken, say Rosenblum, Muirhead and others, with some party leaders even accusing their opponents of treason.

“The key thing going on now is that we have an explicit argument that the opposition party is illegitimate,” says Rosenblum. “Trump has been calling the Democrats the enemy of the people and illegitimate, and saying the election is fraudulent. This is the path to violence, as there’s no way to correct this with another election.”

Political parties throughout the world have lost considerable goodwill and influence, says Shapiro, yet he suggests that rather than ban them or further sap their power we must strengthen them and make them more reliable. He and his colleagues advocate reforming campaign financing, to eliminate the currently chaotic bidding wars for candidates’ loyalties, although that goal continues to be elusive. To combat the rise in extremism, they also urge that the job of redistricting go to nonpartisan commissions instead of gerrymandering pols.

To further reduce the risk of primaries increasing polarization, Shapiro proposes that party leaders be allowed to choose candidates if the turnout in a primary election has fallen below 75 percent of the turnout in the previous general election.

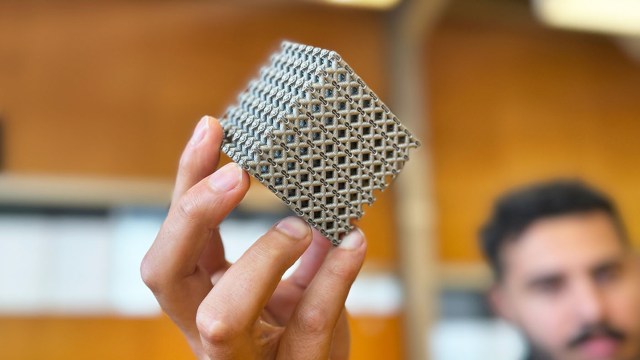

Landemore and her faction contend these ideas don’t match the urgency of the current dilemma. She invites people to imagine how democracy might function with less or even zero reliance on political parties and particularly without costly and potentially corrupting political campaigns. One possibility, she says, would be to randomly appoint groups of citizens, chosen much as today’s juries are, to lead government, while rotating in fixed terms through a permanent “House of the People.” These citizens’ assemblies would be more representative than the current US Congress, wrote Rutgers University philosopher Alexander Guerrero in a 2019 opinion piece for NJ.com, in which he advocated choosing representatives by lottery. “In the United States, 140 of the 535 people serving in Congress have a net worth over $2 million, 78 percent are male, 83 percent are white, and more than 50 percent were previously lawyers or businesspeople,” he wrote.

Several European nations have already tried alternatives to party-driven democracy. In 2019-20, France held a Citizens’ Convention on Climate, calling on 150 randomly chosen citizens to help devise socially just ways to reduce greenhouse gases. In December 2020, French President Emmanuel Macron agreed to hold a referendum on one of the convention’s suggestions, the inclusion of climate protection in the national constitution. And in 2016, the Irish Parliament assembled 99 citizens to deliberate on stubborn issues, including a constitutional ban on abortion. A majority of the assembly proposed that the ban be struck down, after which a national referendum confirmed the result and changed the law — all accomplished without involvement of established political parties.

Despite the limited impact of these efforts to date, Landemore says the tide of public opinion is turning. Just five years ago, colleagues mocked the notion of an “open democracy” at a political science conference, she says, adding: “Five years from now I’m guessing we’ll be completely mainstream.”

This article originally appeared in Knowable Magazine, a nonprofit publication dedicated to making scientific knowledge accessible to all. Sign up for Knowable Magazine’s newsletter.