Mysterious writing system from Easter Island may be completely unique

Rapa Nui, also known as Easter Island, is the most remote inhabited island in the world. This dot of treeless, volcanic land is only 63 square miles wide and sits 2,400 miles off the Pacific coast of Chile. Full of monolithic Moai statues, the island has been intriguing researchers for centuries—and its enigma only continues to deepen with a recent discovery.

People first came to live on the island in the 12th century. Europeans landed on Rapa Nui in the 1720s, and they brought diseases that devastated the population. Then in 1863, the island was raided by enslavers from Peru, and some estimates say only 200 indigenous people survived.

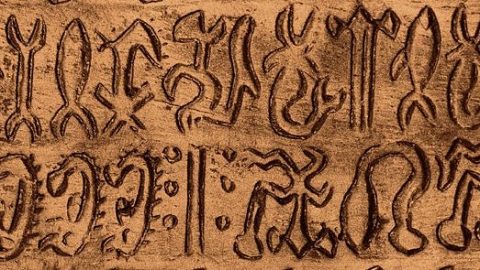

The following year, a missionary named Eugene Eyraud found evidence of Rapa Nui’s written language, Rongorongo, which was intricately inscribed on wooden tablets. Eyraud noted these tablets were seen in every family home and claimed they numbered in the hundreds. However, when Europeans returned a few years later to collect them, only a couple dozen could be found.

Four tablets were sent to a congregation in Rome for preservation, where they remained for over 150 years.

Until now, it was presumed that the Rongorongo script was composed of elements introduced by foreigners. But a team of scientists from Italy and Germany recently found reason to believe the elaborate language predates any European colonization, and it comes with extraordinary anthropological implications.

“Discovering a writing system in such a remote recess is surprising, and debate is still ongoing as to its origins. While it is difficult to prove that contact with literate Europeans was not a stimulus for its creation, its pictorial glyphs do not resemble any known script,” the study stated.

Of the four preserved tablets, radiocarbon dating of the wood determined that three of the tablets were created with trees grown in the 18th or 19th century. Surprisingly, though, the radiocarbon date of the fourth tablet indicated it came from a 15th-century tree—more than 200 years before Europe’s arrival on the island and before the wood was shipped for preservation.

This radiocarbon dating analysis of the wood suggests Rongorongo is an ancient language completely indigenous to Rapa Nui and perhaps even that it was intentionally kept secret from outsiders until the mid-19th century. If so, this would be an example of a previously unknown language—a rare writing system invented without any influence or prior knowledge of other writing.

Further complicating the matter, the wood from the 15th-century tree traveled all the way from Southern Africa, suggesting it might have been driftwood. The authors say it’s unlikely the wood would have been kept for more than 300 years before being inscribed. The engravings themselves, though, cannot be dated, which prevents accurately tracing the history of the Rongorongo language.

“When wood is scarce, islanders might reuse old wood or use driftwood, which could be hundreds of years older than the writing,” said Terry L. Hunt, an anthropologist and Rapa Nui historian. “Archaeologists using radiocarbon dating refer to this as the ‘old wood problem’ given the wood’s in-built age.”

The condition of the fourth tablet is relatively pristine, implying it may have been protected, signifying its importance to the Rapa Nui people.

“If they were maintained on site away from termites and other secondary wood eating insects, then dry wood can be preserved for a long period of time,” said James Speer, a dendrochronologist at Indiana State University. “Wet wood in anaerobic conditions can also be well preserved.”

Dating the emergence of Rongorongo is also difficult because philologists debate what type of script it is. It’s unclear whether Rongorongo is a form of proto-writing or a fully fledged system. It contains an astounding number of pictographic characters—more than 15,000—depticing animals, plants, geometric shapes, and anthropomorphic figures. It’s written in horizontal lines resembling sentences, but in a unique style called reverse boustrophedon, where every other line is upside down.

To this day, Rongorongo is considered undecipherable. Its use was mostly restricted to Indigenous priests, who were eventually captured in the Peruvian invasion, and no one familiar with reading the scripts has since been found.

“One thing is certain,” said Hunt, “We know that the creation of Rongorongo tablets continued into the 19th century, post-dating the arrival of Europeans significantly. Continued cultural practice and persistence of traditional knowledge is noteworthy given the profound impacts suffered by the Rapanui people in post European-contact times.”

This article originally appeared on Atlas Obscura, the definitive guide to the world’s hidden wonder. Sign up for Atlas Obscura’s newsletter.