Rum punch, music, and “election cake”: How to vote like it’s 1799

- Since the Founding Fathers, America has seen many changes in who gets to vote as well as how they vote.

- From new amendments to court rulings against literacy tests, suffrage has become much more inclusive.

- Voting also used to be more festive, with music, food, and rum punch enticing more voters to cast their ballot.

I kicked Election Day off by making myself a large glass of rum punch from Martha Washington’s recipe (orange juice, lemon juice, cloves, cinnamon, etc.). I did this because, for one thing, day drinking was the norm in the 1790s. Booze was especially common during election season. Voting was much more festive then — at least for the privileged few who were allowed to vote.

When George Washington ran for the Virginia legislature in 1758, he provided voters with 28 gallons of rum, 50 gallons of rum punch, 34 gallons of wine, 46 gallons of beer, and 2 gallons of hard cider. He won the election with more than 300 well-lubricated votes.

But mostly, I did it because I needed the liquid courage. I was about to embarrass myself publicly. At 11 a.m., I strode into our local polling station — the high school cafeteria near our home — wearing a black tricorne hat from an Alexander Hamilton costume. I approached a poll worker sitting at a table just past the entrance. She had on a gray sweater and wire-rimmed glasses.

“Hello,” I said, projecting my voice as best I could. “For governor, I would like to vote for Kathy Hochul. And for senator, I would like —”

“Oh, don’t tell me!” she said, cutting me off.

“But I’d like to vote out loud, by voice, like our Founding Fathers did,” I explained.

“No, no, no. You can’t say it in here. You can say it outside, but not in here.”

“But I want everyone to know my vote,” I said. “That’s the way they used to vote in the late seventeen hundreds.”

“Well, times are changing,” the poll worker said.

I glanced at Julie, my wife, who was behind me in line. She was looking down, her hands shielding her eyes.

The woman sent me to another table, where I reluctantly voted the newfangled way — secretly, silently, at a well-shielded desk. (Though perhaps not as newfangled as one would expect in this smartphone-driven world — I filled out the paper form with a ballpoint pen.)

My goal had been to express my constitutional right to vote in the most 1790s way I could.

Let your voice be heard

The Constitution says that “the People” get to vote. Of course, it was notoriously vague on who counts as “the People.” In the beginning, it was mostly White male people, and much of American history was — and remains — the struggle to make “the People” more inclusive.

So “the People” can vote, yet the Constitution doesn’t say how the people vote. There’s no constitutional right to a secret ballot. In fact, the idea of a secret ballot barely existed in early America.

Instead, the Constitution lets the states choose the “times, places and manner” of holding elections, with some oversight from Congress. This setup still has an impact today, as states differ on how easy or hard voting should be. From the 1700s until the mid-1800s, many states had their voters announce their preferred candidate out loud for all to hear. Viva voce, it was called — voting by voice. So that’s what I was trying to do. I wanted to experience originalist voting by voice.

And how did it feel? Humiliating, for sure. But also liberating. I felt like I was smashing the taboo of secrecy. Let the truth come out! Own my opinions. I don’t need to keep my vote private like it’s a case of hemorrhoids.

The loud-and-proud voting method had other advantages, at least from the eighteenth-century point of view. First, it made elections harder to rig. Second, as University of Virginia historian Don DeBats writes, “In those times political choices were understood to be communal, not private, matters. Voting to advance private individual interests calls for secrecy — but public voting made perfect sense when politics was understood to be about group or communal interests.”

I’m not sure voting by voice made you more communal minded. It could have just made you more pressured and intimidated to vote in accordance with your eavesdropping boss. I did find it liberating, but maybe I’d feel differently if my book editor had been in line behind me. In the end, I still prefer the secret ballot, an idea we imported from Australia in the late 1800s, one of that continent’s great contributions along with Cate Blanchett and boxed wine.

The we in “We the People”

Voting by voice isn’t the only difference between today’s Election Day and the founding eras. In fact, if a Founding Father were transported to my polling station, he’d think someone had slipped something into his rum punch.

He would be confused by the sight of Julie, as women didn’t get the national right to vote until the Nineteenth Amendment in 1920. (Though there is an interesting early exception — New Jersey briefly allowed women to vote in 1790 before rescinding the right in 1807. They buckled to media mockery that they were setting up a “petticoat” government. When I told Julie, a Jersey girl, about this, she said, “Well, at least they tried, which is better than New York.”) It wasn’t just women. At the founding, Black people could not vote in most states, whether they were free or enslaved. And Indigenous people could not vote in any state.

The Founding Fathers had profoundly mixed feelings about democracy, [and we] can clearly see the centuries-long battle to expand the vote in the Constitution itself. Or more precisely, in the amendments.

The Fifteenth Amendment, ratified in 1870, gave suffrage to Black men.

The Nineteenth Amendment in 1920 gave the vote to women.

The Twenty-Fourth in 1964 banned poll taxes, which required people to pay a fee before being allowed to vote. The poll taxes had been used as a way to deny impoverished voters, especially impoverished Black voters, their right to vote.

The Twenty-Sixth Amendment in 1971 lowered the voting age from twenty-one years to eighteen. (Fun fact: Jerry Springer, best known for such thoughtful TV topics as “I Married a Horse,” testified before Congress as a young man in favor of the Twenty-Sixth Amendment.)

The Founding Fathers had profoundly mixed feelings about democracy.

A.J. Jacobs

From the 1890s right up to the 1960s, some states gave literacy tests or character tests designed to make it harder for Black people to vote. Often, White voters would be exempted from the tests, which could be ridiculously hard.

Consider the civic literacy test from Sumter County, Georgia, from 1963. You can find it online. There are twenty-eight questions, some incredibly arcane. Here is question 22:

“What does the Constitution of the United States provide regarding the suspension of the privilege of the writ of Habeas Corpus?”

Or number 24:

“What are the names of the persons who occupy the following offices in your county? 1) Clerk of the Superior Court. 2) Ordinary. 3) Sheriff.”

I revised the test to make it fit current-day New York and gave it to Julie, myself, and several of our friends. No one passed. Not even a friend of ours who works in city government.

The Supreme Court ruled that literacy tests were unconstitutional in 1949. But even today, there are still many troubling ways that votes are being suppressed, including lack of voting booths in low-income districts.

Gonna party like it’s 1799

Plenty of things about early-American voting deserve to be left behind — the blatant racism, the sexism, the voting by voice. But I’ve decided that one thing was worth resurrecting: Elections were much more festive, at least for those who could participate.

There were parades, music, and farmers markets. Voting in early America “was an engaging social experience, as voters at the polls talked with friends, threw down shots of free whiskey, listened to lively entertainment, and generally had a good time,” wrote a group of political scientists in the journal Political Science & Politics in a 2007 paper titled “Putting the Party Back into Politics.”

For their experiment, the researchers set up little festivals with music and food at various voting stations around the country. The result? The festivities boosted turnout by almost 7 percent. Which is not nothing.

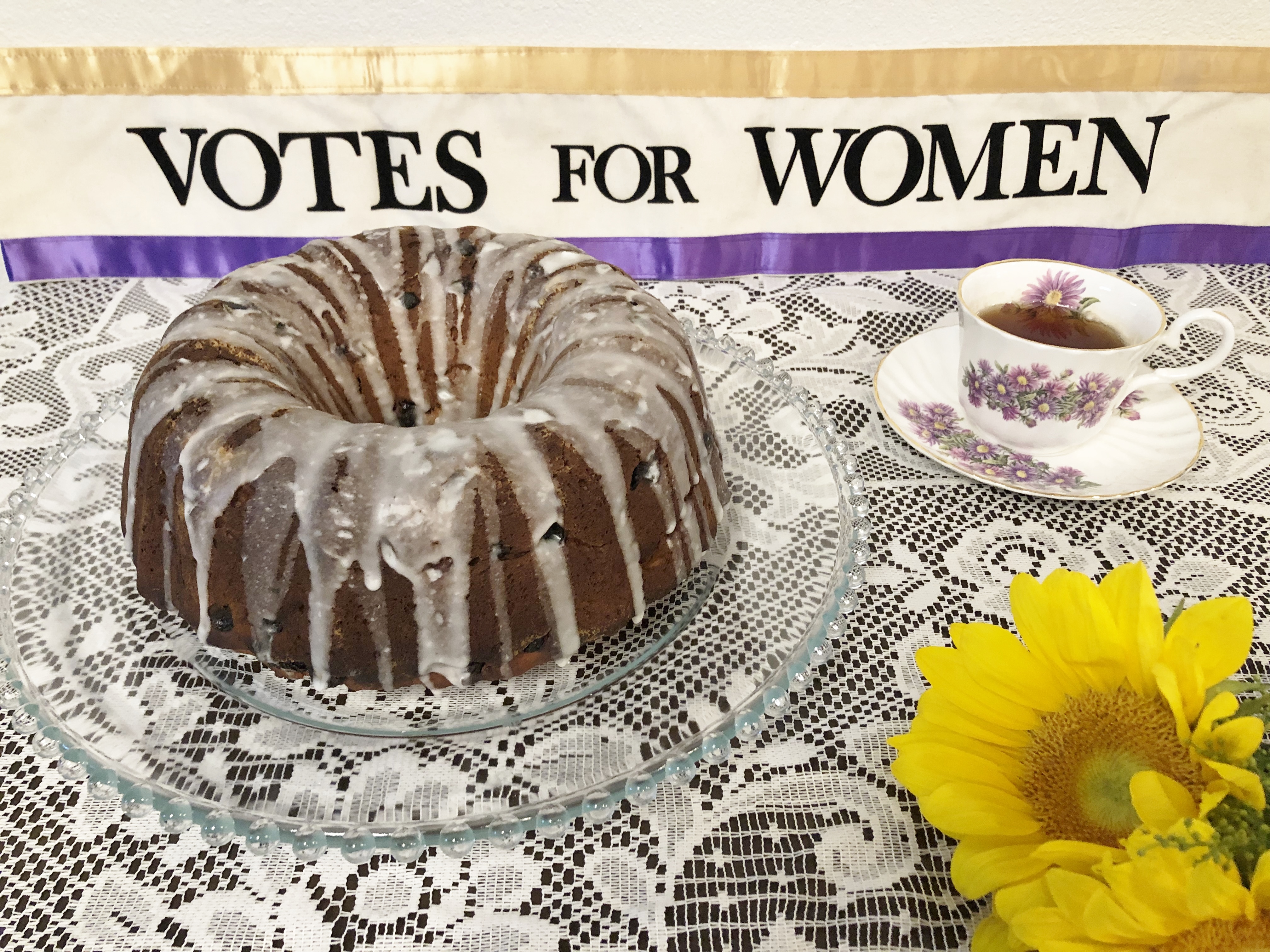

The researchers think we should bring back the good times. And I couldn’t agree more. I want to party like it’s 1799. My plan was to reintroduce an early-American treat: the election cake. Americans would bake cakes and hand them out at the polls. The first known printed recipe for election cake was in a 1796 edition of a cookbook called American Cookery. I found the recipe online. In addition to the usual cake dough, an election cake is filled with figs, cinnamon, cloves, raisins, and nutmeg.

My niece has a side hustle of baking cakes, and she said the recipe sounded inedible. I was not deterred. Right after I voted, I went to the grocery store with my son Zane to pick up the ingredients. We came home, chopped the figs, baked the cake, topped it with red-white-and-blue icing, and tried a piece. Not bad! Tastes like participatory democracy! Actually, the spices make it taste vaguely like Worcestershire sauce.

We carried the cake to the polling station near our apartment and set up a table with forks and napkins and paper plates on the corner by the poll entrance (one hundred feet away, as required by current New York law).

“What’s this?” asked a curly-haired woman. She was on the corner by our table, handing out pamphlets for something called “the Medical Freedom Party,” an anti-vaccine group.

“I’m trying to revive the eighteenth-century tradition of election cakes,” I said. “I’m trying to make voting more festive.”

“Is it gluten-free?” she asked.

Democratic icing on the cake

We successfully gave away every slice, and I considered the election cake experiment a victory. In fact, I decided to go bigger for next year’s election. What if we blanket the country in 2023 with festive cakes to celebrate suffrage? Maybe come up with a catchphrase like “Democracy is sweet”? Part of my goal for this project is to figure out not just what is outdated from the founding era but also what might be worth reclaiming.

Election cakes are a great candidate. To be safe, I’ll skip the rum punch.