Effective altruism is stumbling. Can “moral ambition” replace it?

- Over 25% of workers in rich countries don’t think their job has any meaningful societal value.

- This might be because the currency of success has been shifting from moral ambition to money over the years.

- In his new book Moral Ambition, the Dutch sociologist and historian Rutger Bregman makes the case for how to live a more fulfilling life while making the world a little better in the process.

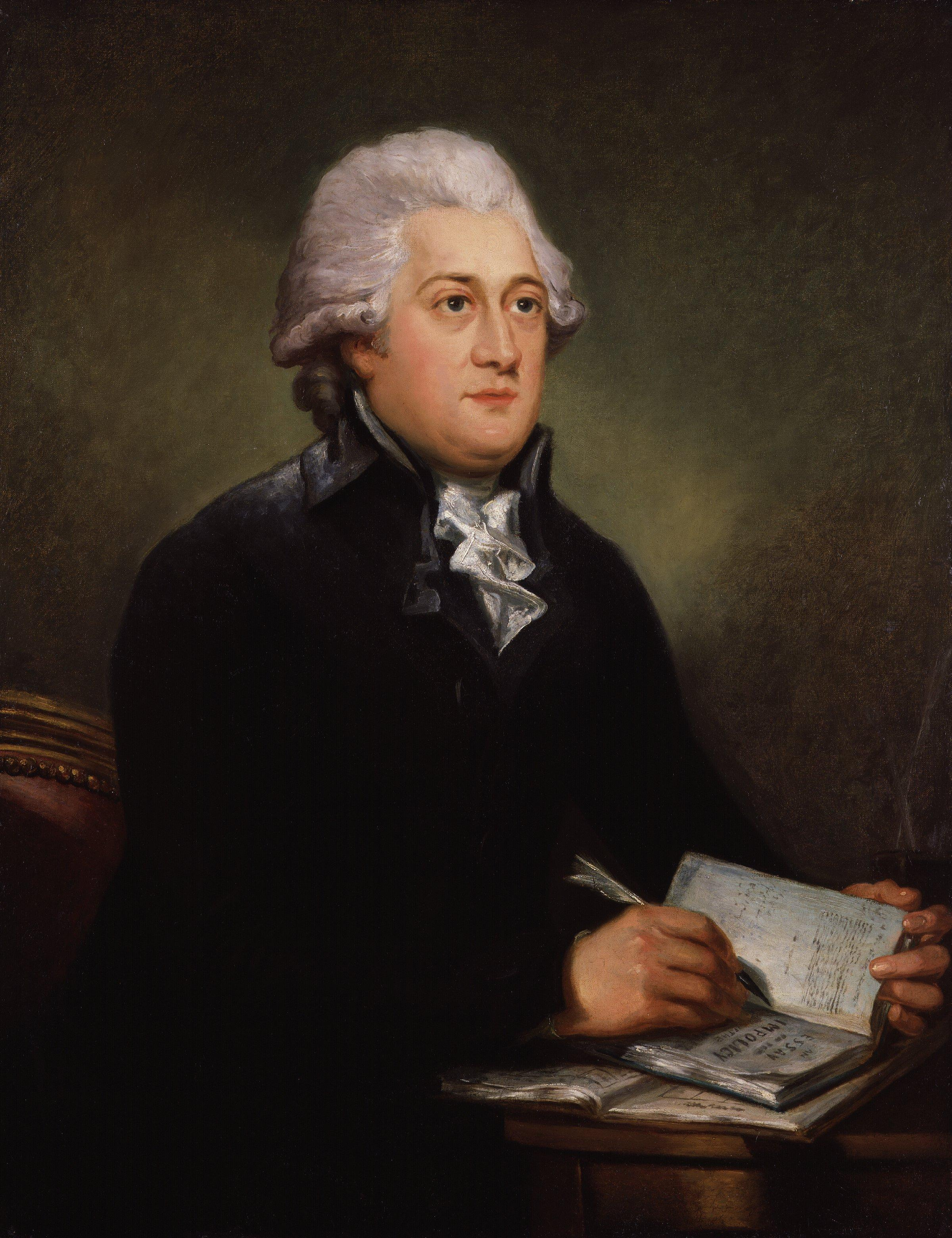

In 1785, a 25-year-old student at Cambridge University named Thomas Clarkson participated in a Latin essay competition about the immorality of slavery. Raised in a sheltered, upper-class environment, Clarkson knew little of the practice at the foundation of the British Empire’s wealth and power. But the more he read about the inhumanity African slaves endured both during and after their passage to the Americas, the more it affected him. Channeling his outrage into his writing, Clarkson ended up winning the competition, a victory which in retrospect marked the beginning of his lifelong career as an abolitionist.

According to Dutch journalist and best-selling author Rutger Bregman, Clarkson represents something we are sorely missing in today’s world: a willingness among young people to use their talent and ambition for the common good instead of personal profit and status. While some fall down social media rabbit holes about dropshipping, lured by the promise of getting rich quickly without making a meaningful contribution to society, others slave away in designer-furnished offices, working jobs that, though hard-earned and well-compensated, lack a clear meaning and purpose.

What to do instead? Create a new standard of success by shifting your ambition away from money and toward finding solutions for the world’s most pressing problems. That’s the main argument in Bregman’s Moral Ambition, which he described as an “almost embarrassingly ambitious book that aims to be the start of a new movement.”

One of the most widely read and discussed books in the Netherlands at this moment, its case studies explore some of history’s most successful activists — including Clarkson — and aim to restore faith in human agency and ingenuity, marrying socially conscious activism with good, old, capitalist entrepreneurship. With an English translation set to release next year, Bregman shares why his message isn’t just pertinent for Dutch readers, but American ones, too.

Redefining success

Bregman first tapped into the Dutch zeitgeist with his 2019 book Humankind: A Hopeful Story, a Yuval Noah Harari-esque mashup of history, sociology, and psychology which argues that, no matter how horrible the human race is made to look in the news, most people are – fundamentally – good. At the time, Bregman hoped this positive outlook would alleviate some of the pessimism and cynicism he saw around him. But while it gave his readers hope, it also made them more complacent.

“At some point I saw influencers positing images of themselves on social media reading Humankind on a beach in Bali and writing, ‘What a lovely holiday. My faith in humanity is completely restored. I’m going to work less and just enjoy my life,’” he tells Big Think. “I felt I had created a monster. If my previous book was like a warm hug, then I felt my next one should be a cold shower. Cold, but refreshing and energizing.”

True to this promise, the first chapter of Moral Ambition is titled, “No, you are not good the way you are.” At first glance, such a sentence seems more at home in a Jordan Peterson book than in the writing of a progressive like Bregman, but where the conservative psychologist uses it as an argument for why people – particularly social justice warriors – should leave each other alone, Bregman’s is a call to action and involvement: a call for professionals to quit their “bullshit jobs” at banks and consultancies in favor of a career with a bigger, more meaningful social impact, and for professional activists to set aside their differences and become a little more pragmatic in the way they go about reaching their idealistic goals.

Bregman doesn’t define “bullshit jobs” based on personal opinion, but scientific research. “My main argument is there’s a huge waste of talent going on,” he reiterates. “So many people are stuck in jobs that don’t have much societal value. And that’s not me saying that. It’s them. There’s a famous study by Dutch economists Robert Dur and Max van Lent, who used a huge international data set to estimate that around 25% of the workforce in rich countries believes their own job is useless, or what the late anthropologist David Graeber called “bullshit jobs.” If these people — marketers, consultants, corporate lawyers — focused on tackling the world’s most important issues, they could accomplish great things. But that’s just not the case.”

Things weren’t always this way. In his book, Bregman writes about various activist movements from the near and distant past who, through their perseverance, helped make moral ambition fashionable, including Clarkson and the abolitionists, which grew out of a progressive 17th-century Christian group known as the Quakers, the civil rights demonstrations spearheaded by Rosa Parks, Malcolm X, and Martin Luther King, Jr., and Ralph Nader’s fight against corporate America. These movements, particularly the latter two, had a huge effect on youth culture:

“In the 1970s, a survey asked college students in the US about their personal goals. Between 70 and 80% of them answered that their biggest goal was to develop a meaningful philosophy of life, while between 40 and 50% answered it was making money.”

Presently, Bregman continues, those percentages have more or less reversed, though not necessarily for the reasons you would think. “Obviously there are some structural factors at play. Inequality has grown and housing costs have exploded. But I don’t think that’s the whole story, because you can see the same pattern among both really privileged students who come from wealthy backgrounds and less privileged students. For the latter, it makes sense that you would prioritize making a lot of money because you have to pay back your huge student loan. But for others, it doesn’t make that much sense. I think what has happened in the last couple of decades is that we have developed a definition of success that is about getting a high salary, a fancy job title, a corner office. That’s a purely cultural phenomenon. It’s not human nature. It doesn’t have to be this way, and I think we can change that.”

A solution may present itself in the unlikely marriage between the idealism of a professional activist with the ambition and practicality of an entrepreneur. Just as a business looks for holes in the market when developing a new product, so does Bregman urge these would-be activist-entrepreneurs to focus on pressing but overlooked global issues. In his book, he shares the story of Rob Mather, a successful strategy consultant from London who – after organizing a charity swim for a burn victim he saw on television – went on to found the Against Malaria Foundation because, while a cure for the infectious disease already existed, it wasn’t being made available to the countries that needed it most.

Bregman also praises the practicality of Clarkson who, realizing that his fellow Brits did not see African slaves as human enough to care about their suffering, sought to abolish the slave trade by standing up for the health and safety of the crew transporting those slaves – a morally reprehensible argument to some, but one that proved effective as, in 1807, Britain became one of the first European countries to abolish the slave trade.

Moral ambition in America

Bregman has co-founded an organization, The School for Moral Ambition, that helps talented people get out of meaningless or harmful jobs, and aims to make ‘moral ambition’ a well-known lifestyle, just like minimalism or mindfulness. Currently, Bregman and his team are planning an international expansion, with Bregman preparing to relocate with his family to New York City.

He believes his book is even more relevant for the United States than it is for the Netherlands, not least because his thesis should appeal to both sides of the political spectrum. Those on the right will likely resonate with the (neoliberal) assumption that the biggest societal changes come from the actions of small groups of individuals on the ground, rather than top-down reforms of the societies they inhabit.

“Moral pioneers in the US and the UK, including the abolitionists, demonstrated that small, committed, idealistic groups of people could make a massive difference,” Bregman explains. “They weren’t stuck analyzing structural problems. They weren’t saying, oh, it’s all the fault of capitalism. It’s all the fault of the elite. Nelson Mandela said it’s relatively easy to change the world. It’s much more difficult to change yourself. Often that is regarded as a right wing, neoliberal thing to say. People on the left say no, everything should start with the system, with the structural causes of poverty and inequality. At some point I became frustrated with that way of thinking because it seems to be an excuse to keep pointing at others. But then what do you do yourself?”

“Never doubt that a small group of thoughtful committed citizens can change the world,” said cultural anthropologist Margeret Mead. “In fact, it’s the only thing that ever has.”

Left-leaning readers will see Moral Ambition as a call to action – they have already answered that call – but as a guide for how to put their ideals into practice, and how not to. “Awareness is so overrated,” Bregman says of a term that’s thrown around a lot these days. “It doesn’t matter that your timeline is full of the right opinions about all the things happening in the world. It’s easy to go viral by shouting at billionaires – look at me – but does it accomplish anything?” He also argues a lot of activism is being expressed in negative as opposed to positive terms; instead of eating lessmeat, fund, join, or found a company that produces green, lab-grown meat.

Last but not least, Moral Ambition should appeal to American audiences because it can replace an older and, in Bregman’s opinion, a misguided movement that sought to weaponize the country’s capitalist engines to protect the planet and the human race: effective altruism. Born from a thought experiment by philosopher Peter Singer — if you would ruin your expensive sneakers to save a child drowning in a river in front of you, why wouldn’t you donate money to save a child starving in another country? — effective altruism encourages talented, ambitious young people to embrace their inner capitalist, maximize profits, and then donate those profits to accomplish the maximum amount of good.

Bregman saw EA’s demise long before the downfall of the movement’s poster child, Sam Bankman-Fried, who through his cryptocurrency exchange FTX was behind one of the biggest frauds in US history. Although there are some things about EA that Bregman admires, like its support of non-profit charity entrepreneurship, he says the movement ultimately “always felt like moral blackmailing to me: you’re immoral if you don’t save the proverbial child. We’re trying to build a movement that’s grounded not in guilt but enthusiasm, compassion, and problem-solving.”

The happiest man in the universe

In the prologue of Moral Ambition, Bregman recounts the story of Matthieu Ricard, a French molecular geneticist who – after receiving his PhD – traveled to the Himalayas to become a Tibetan Buddhist monk. Later in life, Ricard participated in a famous study from the University of Wisconsin-Madison, where an MRI scan of his brain revealed that the parts of his brain responsible for feelings of joy and satisfaction were working overtime, while those responsible for feelings of pain and sadness were virtually dormant. Celebrated in newspapers as the “happiest person in the world,” Ricard became an exemplary figure for many – but not Bregman.

“Here’s a person who spent 60,000 hours meditating before becoming the most emphatic man in the universe,” Bregman says. “The neurologists said, ‘Holy shit! We’ve never seen anything like that!” But when I read the story for the first time, I got a bit angry. The world is burning, people are dying, and you’re meditating. To me, that’s not super admirable.”