How to understand all the talk about a “crisis in cosmology”

- Cosmology differs from other sciences because it studies the entirety of the Universe. Any significant change in its understanding raises deep philosophical questions.

- Cracks have occurred in the standard model of cosmology. Fixing it might require small tweaks to the theory or a complete overhaul.

- When we speak of a “crisis” in science, this is not a bad thing. Instead, it is an exciting opportunity to discover new aspects of nature.

Human beings need origin stories, which is why every human culture has an origin “myth,” a narrative of how the Universe was born and how it came to be the way it appears today. We moderns, however, developed science, which is a particularly powerful way to enter into dialogue with the world.

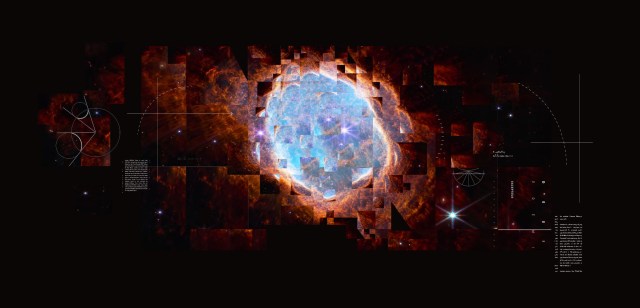

Our scientific origin story is something called the standard model of cosmology. It is justifiably seen as a triumph of reason and human imagination. Recently, however, in light of new data and other theoretical considerations, the idea of a “crisis in cosmology” has been getting attention. This essay, the final in a series I’ve been doing here at Big Think, is meant as a kind of summation of where we stand right now in that question.

Is there a crisis in cosmology?

This attempt at summation also comes in the wake of a very recent New York Times op-ed Marcelo Gleiser and I wrote on the subject. It received a lot of attention (mostly favorable, I’m happy to say), but the point is that it was driven by and informed through the topics I have been exploring in this series. Today, I want to do a deeper dive into some of the issues we raised there and connect them to what we have been unpacking here in our exploration of the state of the standard model.

Let’s start with the 10,000-foot (or maybe the 10,000-parsec) view. I began this series based on a really interesting paper by astrophysicist Fulvio Melia entitled “A Candid Assessment of Standard Cosmology.” Melia’s actual assessment is pretty negative. As he puts it, “The standard model needs a complete overhaul in order to survive.”

I was actually led to this paper via a nice essay on it by Ethan Siegel who, while he disagreed with Melia’s pessimism, reviewed the questions Melia raised favorably, saying that, “There are incontrovertibly very real problems within the concordance model of cosmology, whether you think it needs a complete overhaul or not… It’s important to recognize that the gaps in our understanding are substantial, and some of them could offer clues that lead us to a better understanding of our universe as a whole.”

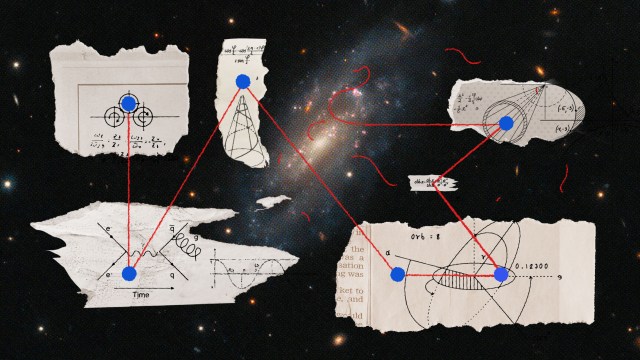

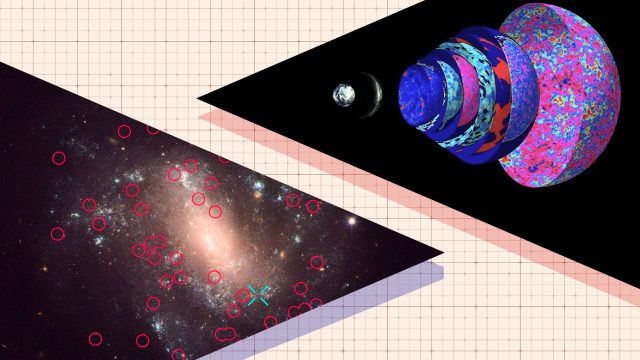

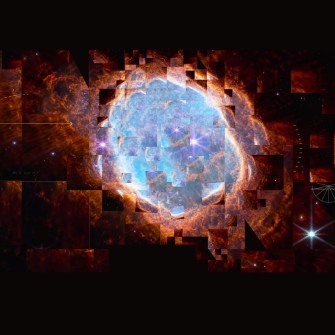

In his paper, Melia listed a set of problems both observational and theoretical associated with the standard model that he thinks pose major challenges. These include: the now famous and very challenging Hubble tension; the question of too-early black hole and galaxy formation; the question of initial conditions and entropy; and problems with inflation and the cosmic microwave background. In the previous posts in this series, I have tried to explore some of these issues. In the wake of their totality, Melia acknowledges that the standard model does show some spectacular successes in terms of the match between data and theory. But, he argues, some of this success comes because the model has so many knobs (free parameters) that refining their values via observations is not teaching us anything fundamental.

So, the question, “Is there or is there not an actual crisis in cosmology?” seems to be a matter of commitment to the standard model in its current form. It does seem to me that there are some “incontrovertibly very real problems.” But what happens next is where things get interesting. That’s what Marcelo and I were exploring in in our op-ed and what I want to unpack a bit deeper here as a way of closing our series.

Cosmology is unlike the other sciences

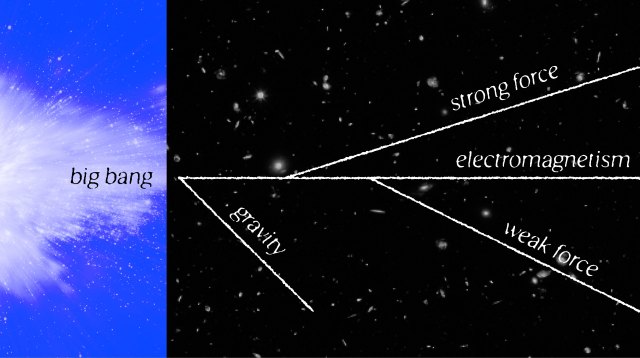

Marcelo and I wanted to explore a question which might be phrased: What happens if we do have to overhaul cosmology? The thing to note here is that cosmology is not like other sciences. Back in the 15th and 16th centuries, the founders of the scientific method were keen to show how you could take parts of the world, isolate them, and then probe them in controlled experiments. Francis Bacon called this “vexing” a phenomenon. Basically, you isolate the thing you want to study and then poke it. The method works great for lab studies of everything from particle physics to chemistry to biology. Even when you cannot isolate or even control your subject of study, as in geology or astronomy, you can look at many different examples of it to draw statistical conclusions. If you are interested in how volcanoes work, look at lots of different volcanoes. If you are interested in how stars work, look at lots of different stars.

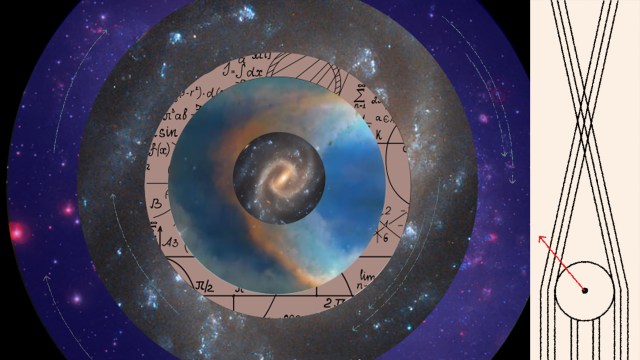

Cosmology, however, is an entirely different ball game. We define the Universe to be all there is. So, unless you want to imagine a bunch of unobservable universes that allow you to pretend you can do statistics on them, you are stuck with the one we live in that includes all space, time, matter, and energy. The “all” in that last sentence is what really makes the consequences of having to reboot a cosmological model so consequential. As Marcelo explored in his book The Dancing Universe, there are only a limited set of logical options for dealing with the origin and evolution of everything. Each one of these has its own philosophical issues, like what it means to start a Universe from “nothing.” What do we even mean by nothing? Can there really be nothing? This is why any big change to cosmology could take us headlong into some profound philosophical questions, the kind that have been floating around inside human heads for millennia.

But there is another possibility, one which Marcelo and I were careful to address multiple times and which we can unpack here too. The problems with the standard model may be solved by simply finding adjustments in the model. That, in a sense, is what has been happening for the last 40 years. The classic Big Bang model showed a number of paradoxes associated with the link between the early and modern Universe, so cosmologists added inflation. The luminous matter we could see was moving in ways we could not understand, so we added dark matter. The Universe was unexpectedly accelerating, so we added dark energy. These were big adjustments to the classical Big Bang model, which is built on the Universe’s expansion and its evolution from a hot dense soup of particles (two things that are absolutely not in doubt). Maybe some of the problems we are seeing today can be handled by smaller adjustments. If that happens, then what people are calling the “crisis in cosmology” will turn out to be something far less dramatic.

In science, a crisis is exciting

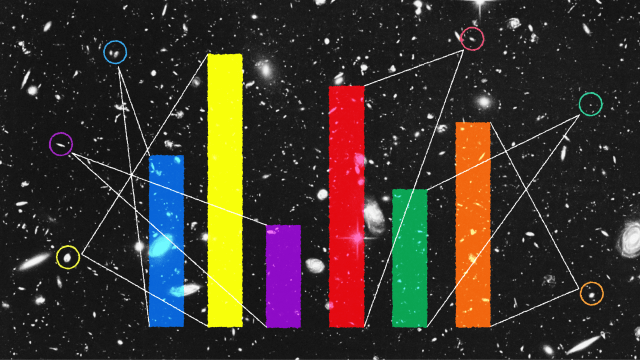

So, what’s it going to be? As of this moment, I think it is too early to tell. The standard model has been successful enough that it makes sense for most astrophysicists to stick with it. But if the Hubble tension cannot be resolved, if no dark matter particle shows up after another decade or more of searching, and if the issues with inflation that Melia raised remain, then things may change. Over time, astrophysicists will begin exploring alternatives more seriously.

And that leads us to our final point. The whole idea of a “crisis” gives the wrong impression of what happens when a paradigm (in this case, the standard model of cosmology) begins to show problems. It is not a disaster filled with dread and anxiety. Instead, it’s really exciting! What could be cooler than standing at a frontier where nature is trying to show you something new and dramatic?