An end to doomerism

Pessimism sounds smart. Optimism sounds dumb. It’s no wonder, then, that pessimistic messages hit the headlines, and optimistic ones hardly get a middle-page snippet. It’s why doomsday thinkers get respect and accolades. They’re the smart ones that can see what the rest of us can’t. They’re the ones that speak truth to power.

I’ve fallen into this trap myself. I saw cynicism in other people and mistook it for intelligence. To look smart, I tried to do the same. I went through a period of playing life like a game of whack-a-mole. Any idea – promising or not – had to be smashed out of sight. It was doomed to fail.

There is an “optimism stigma” that is pervasive throughout society. It’s why I often feel embarrassed to admit that I’m an optimist. It knocks me down in people’s expectations.

But the world desperately needs more optimism to make progress, so I should stop being so shy about it.

The possibility of progress

The issue is that people mistake optimism for “blind optimism” — the blinkered faith that things will always get better. Problems will fix themselves. If we just hope things turn out well, they will. Blind optimism really is dumb. It’s not just stupid, it’s dangerous.

The issue is that people mistake optimism for ‘blind optimism’ — the blinkered faith that things will always get better.

If we sit back and do nothing, we will not make progress. That’s not the kind of optimism that I’m talking about.

Optimism is seeing problems as challenges that are solvable; it’s having the confidence that there are things that we can do to make a difference. “Urgent optimism,” “pragmatic optimism,” “realistic optimism,” “impatient optimism” — I’ve heard many terms for this concept.

To make my case for why optimism is so essential for progress, we need to understand the positions of optimists versus pessimists. The definition of pessimism is “a tendency to see the worst aspect of things or believe that the worst will happen.” Optimism, on the other hand, is the “hopefulness and confidence about the future or the success of something.”

People mistakenly see optimism as an excuse for inaction. They think that it’s pessimism that drives change, and optimism that keeps us where we are. The opposite is true.

Optimists are the ones that move us forward. They are the innovators, the entrepreneurs, the ones willing to put their reputation, money, and time on the line because they see an opportunity to solve a problem.

Pessimism blocks solutions. If we always believe that the worst will happen, then what’s the point in starting? If any action will fail, we should stick with the status quo. Follow the pessimists if you want the world to stagnate or regress.

People mistakenly see optimism as an excuse for inaction. They think that it’s pessimism that drives change, and optimism that keeps us where we are. The opposite is true. Optimists are the ones that move us forward.

The reason pessimists sound smart is that it’s hard to prove them definitively wrong. Pessimists are a moving target. If they predict that a technology will fail, and it succeeds, then there is always another reason why it won’t work. It might have solved one problem, but it won’t solve all of them. Or it might work for most people, but it won’t work for everyone.

There are almost limitless opportunities to shift the goalposts. A pessimistic stance is a safe one. There is often little to lose.

But it’s critical not to conflate criticism and pessimism

Optimism is risky. It exposes us to failure. In fact, repeated failure is a given. That’s why it looks dumb from the outside. If we try to launch a rocket into space, and it’s a non-starter, someone gets blamed. If we try 99 designs for a new high-yielding crop variety, or a vaccine against malaria, we might fail 99 times.

We might even spend our entire career without a single breakthrough. There’s a downside to optimism. But the potential upside is much, much bigger. The 100th attempt at a vaccine might be the winner. The optimism to keep going might save hundreds of millions of lives.

One reason that admitting I’m an optimist feels like unearthing a dark secret is that it seems like it goes against years of scientific training. Pessimism is often regarded as an essential feature of a scientist: the basis of science is to challenge every result, to pick theories apart to see which ones stand the test of time. I thought that cynicism was one of its founding principles.

Maybe that is partly true. But science is undeniably optimistic, too. How else would we explain the willingness to try experiments over and over, with slim odds of success?

Scientific progress can be painfully slow: the best minds can dedicate their entire lives to a single question and end up with nothing to show for it. They do so with the hope that they might be on the cusp of a breakthrough. It’s unlikely that they will be the person to discover it, but there’s a chance. Those odds drop to zero if they give up. Optimism lies somewhere in the hearts and minds of scientists.

That’s why we shouldn’t mistake criticism for pessimism. Effective optimists need criticism. It’s essential. We need to cut through ideas to find the most promising ones. We need to trim back the long list to find the ones that are worthy of our time and resources. We need to identify the weak points to redesign them for success.

Most innovators that have changed the world were optimists. But they were also fiercely critical: no one picked apart the ideas of Thomas Edison, Thomas Edison, Boyan Slat, Norman Borlaug, or Marie Curie more than themselves.

That’s why we shouldn’t mistake criticism for pessimism. Effective optimists need criticism. It’s essential.

When pessimism leads to doomerism it has a real cost

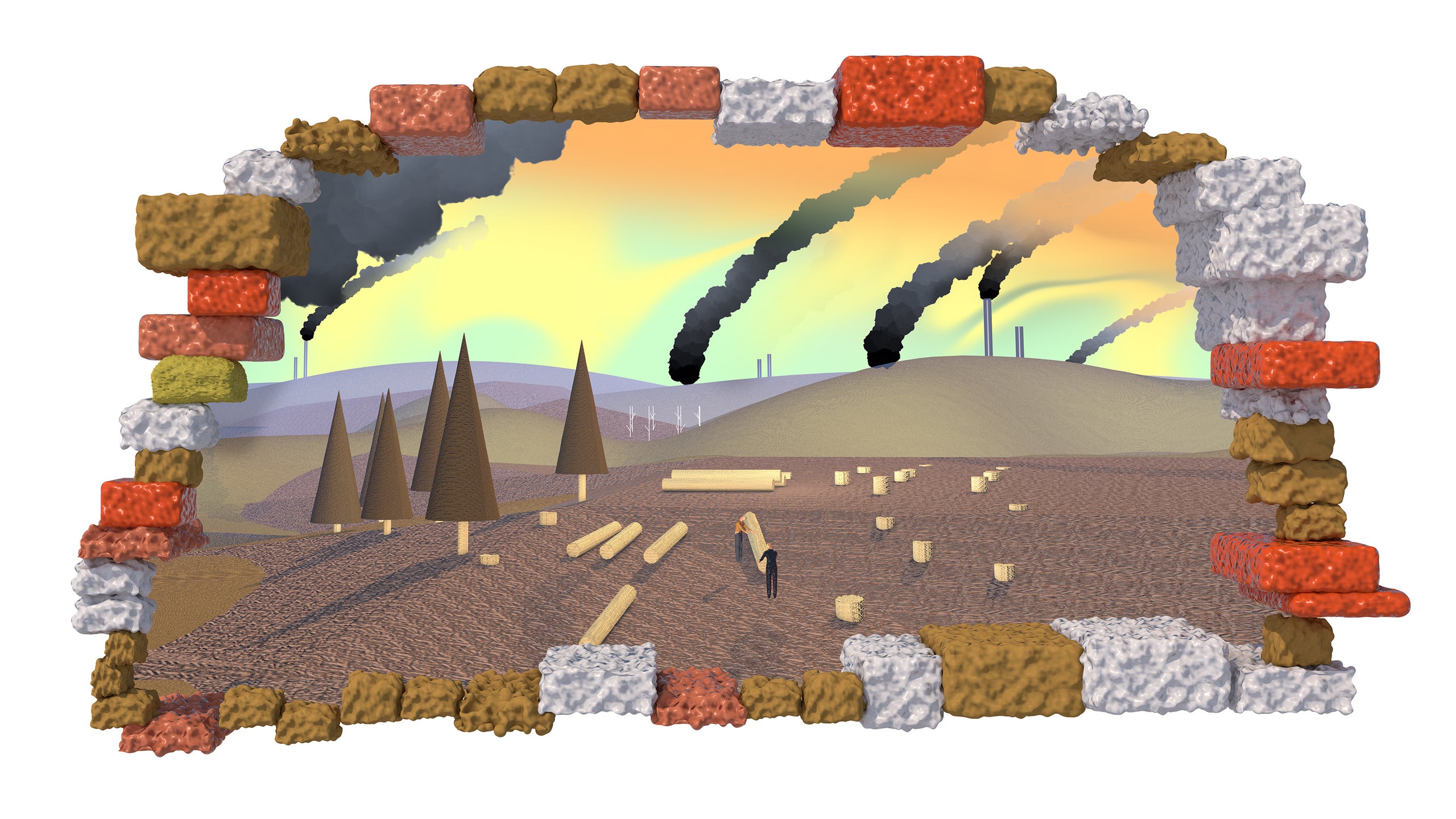

Pessimism around progress has seeped into almost every grain of society. But I see it most clearly in my own field – environmental science. There, the feeling of doom is even harder to shake. That’s because, while most markers of human progress – whether that’s health, education, or poverty – have been moving in a positive direction, most environmental metrics have been going backward.

To some extent, environmental costs have been collateral damage to human progress. Last year I wrote an article in WIRED – Stop Telling Kids They’ll Die From Climate Change – that tried to push back on the growing doomism about our future in a changing climate.

I argued that the message we tell our kids about climate change is not just cruel, it also gets in the way of progress. The majority of young people today feel anxious about what the future will look like as a result of climate change. Many think “humanity is doomed.” Some are hesitant to have kids.

Of course, they get this feeling from the messages they’re told from leading activist voices. This message is not just wrong, it’s also counterproductive.

We give up when we feel like progress is impossible. If a problem can’t be solved, then where is the incentive to work on it? In a time when we need the world’s smartest and most creative minds working on a pressing problem, we turn them away from it by telling them a false story. They give up — or they reach for extreme solutions that just won’t get societal buy-in.

In reality, it is possible to solve our environmental problems. Climate scientists certainly think so. They are often less pessimistic than the general public, which is a new and odd disconnect.

They have children, and believe that they have a future worth living for. They continue to push for action and solutions every day. Few accept that humanity is doomed.

Why would they be more optimistic than the public? Perhaps it’s because they have seen substantial progress in their lifetime. They have been shouting for the world to take action for decades, often with little success.

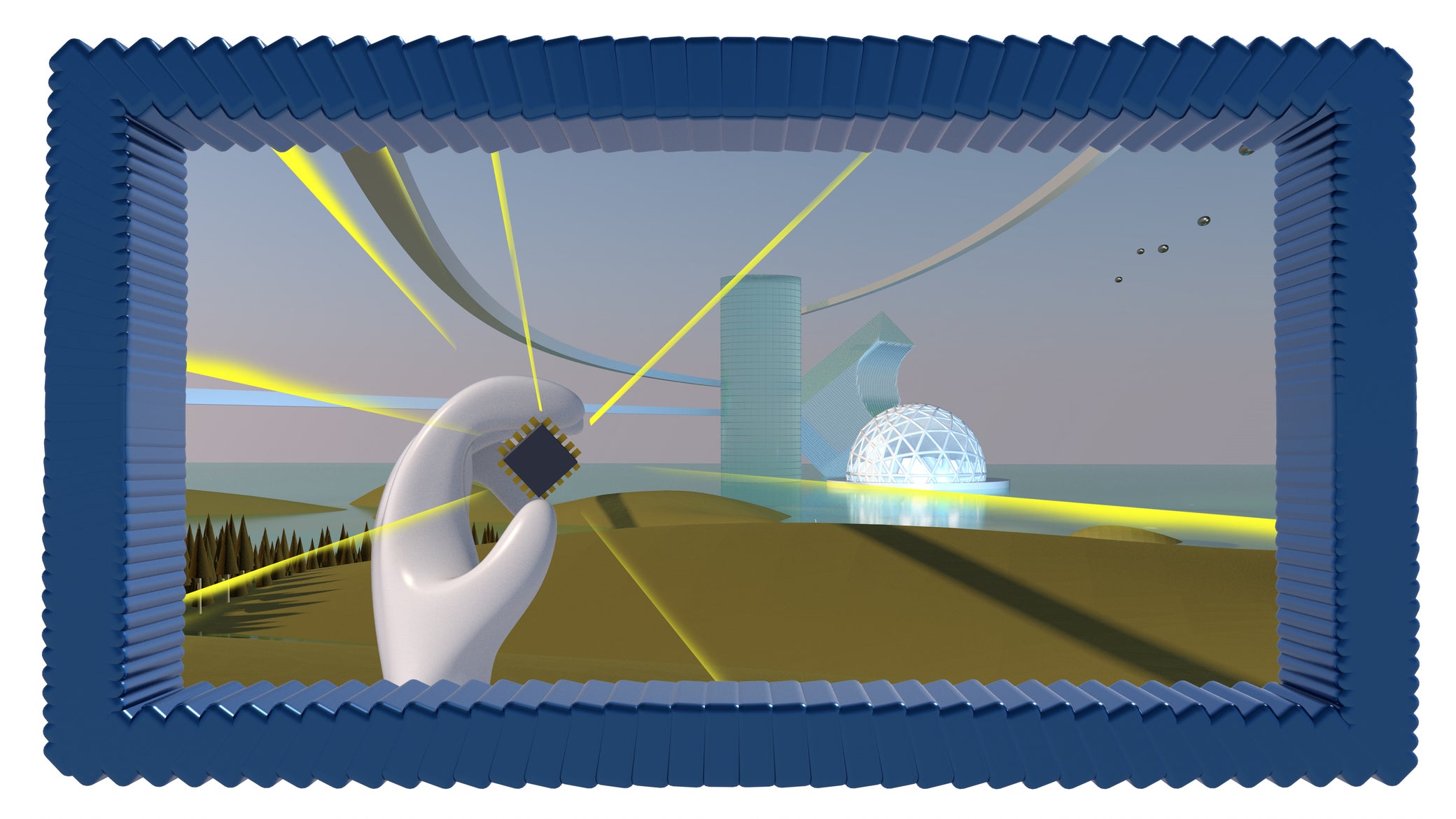

But, in the last few years, things have been moving quickly. They’ve seen countries progressively raise the stakes of their climate targets. Private companies have become more ambitious about sustainability.

We give up when we feel like progress is impossible. If a problem can’t be solved, then where is the incentive to work on it? Climate scientists certainly think [it’s possible to solve our environmental problems]. They are often less pessimistic than the general public, which is a new and odd disconnect. Few accept that humanity is doomed.

They’ve seen the cost of renewable energy and batteries plummet. They’ve seen the public wake up to the realities of climate change. It has moved from the fringes to the mainstream. Almost no climate scientists would say that this is enough. It’s obvious that we’re not moving fast enough.

But at least they’ve seen progress happening. They’ve seen the transition from inaction to action. And that gets to the root of why “progress studies” is so important.

To believe that more progress is possible, we need to have seen examples of it in the past. When we see things moving forward, it evolves from fictional utopia to reality. What separates optimists from pessimists is that the optimists study success stories. They first acknowledge that progress has happened. They then dig in to figure out why: what worked; what didn’t work; and what can we learn to tackle other problems?

Pessimists are completely blind to progress. That blindfold not only robs them of the energy to push forward, it also robs them of the lessons on how to do so. Pessimism might sound smart, but it doesn’t give us smart results. If you’re on the fence about your pessimistic-optimistic stance, take a step back and question whether you’re more interested in sounding effective, or being effective.

I’ve seen this dynamic play out for our environmental problems. But you’ll find it in almost every discipline. As countless famous polls from Hans Rosling and Gapminder have shown, most people are too pessimistic about the world. Most think that the world is getting worse: they believe extreme poverty, child mortality, and access to education are all worsening. In reality, the opposite is true.

Don’t forget your history

Knowing that the world has moved forward is the starting point for positive change. When we look at surveys, we find that those who know the most about global progress tend to be much more optimistic about the future.

26,000 people across 28 countries were quizzed on basic questions about global development, and then asked “Over the next 15 years, will the world be better off, or worse off?”

Nearly two-thirds of those with “very good knowledge” (getting five or more answers correct out of eight) thought the world would be better off. Just 17% of those with “no knowledge” (getting no answers correct) thought it would be.

If we’re serious about tackling the world’s biggest problems, we need to be more optimistic.

Of course, these are just correlations. But it seems that recognising past progress is a prerequisite for belief that the future can be better than it is today.

If we’re serious about tackling the world’s biggest problems, we need to be more optimistic. We need to believe that it is possible to tackle them and lean in – critically – to the things that will make that vision a reality.

The realistic case for optimism is not unfounded. There are countless examples – from poverty and health, to technology and environment – of positive change. Rapid change, too. We should be impatient about changing them faster. To drive progress, we need to become impatient optimists.